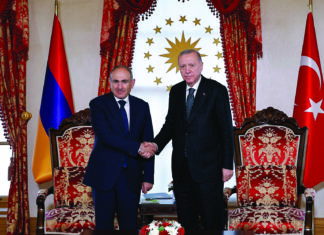

BERLIN — The “Yes” vote in the Turkish referendum may turn out to be a Pyrrhic victory for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Not only was the reported margin in favor of the constitutional changes far slimmer than Erdogan’s AKP party and pre-election polls had expected, with only 51.4 percent of the vote, but the political fallout in Europe may be profound.

In Germany, which has the largest Turkish community in Europe, the political class clearly favored a “No” vote, on grounds that the constitutional changes would grant Erdogan the status of President-for-life currently enjoyed by some potentates in Asia and Africa; not only would he be able to occupy the bombastic presidential palace for more than another decade, but he would be able to rule virtually unopposed by parliament or other political institutions. The blatant violations of human rights and basic civil liberties, especially since the attempted coup last summer, have left no doubts about the policy options that the super-president will pursue.

German leaders responded cautiously but clearly to the first news of results. Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel advised all to maintain “cool heads” and to proceed with prudence. And in a joint statement issued by him and Chancellor Angela Merkel on April 17, the message was that Berlin expected the Turkish government to “seek a respectful dialogue with all political and social groups in Turkey.” They said the very close vote meant a “huge responsibility for the Turkish leadership and for President Erdogan personally.” Following weeks of Germany-bashing by Erdogan, who went so far as to accuse Merkel et al of Nazi methods, the popularity of the Turkish president in Berlin had hit rock bottom. But that is not the primary concern for Germany’s politicians. As reflected in commentaries by experts on election night, there are reasons to fear that Turkey, now divided as never before, could become the theater for violent political conflict.

EU Shuns Dictatorship

The clearest message issued by German politicians was that the transition to one-man rule in Ankara would snuff out whatever hopes remained of Turkish entry into the European Union. CSU chairman Manfred Weber said “full membership for Turkey could no longer be the goal,” and that European heads of state and government would have to review their relationship to Turkey at their upcoming meeting in two weeks. The deputy chairwoman of the CDU, Julia Klöckner echoed this view, saying “the door to an EU membership is now definitely shut,” adding that financial support for the process would also end. European politician Elmer Brok, also from the CDU, was more cautious, in light of the fact that such a large portion of Turkish voters had voted against the changes. He did, however, stress that if Erdogan were to make good on his promise to reintroduce the death penalty, that would terminate the EU access process immediately.

On the left of the German political spectrum, demands for concrete action prevailed. Both the Left Party and the Green Party called for Germany to withdraw its 260 troops currently stationed in Incirlik and to halt all weapons deliveries to Turkey. Cem Özdemir, co-chair of the Greens, directed his attention to the Turkish voters in Germany, 63 percent of whom had voted “Yes.” His message was that those living here would have to commit themselves fully to upholding the constitution, the German constitution that is.