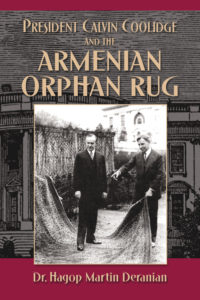

WASHINGTON (Washington Post) — The rug was woven by orphans in the 1920s and formally presented to the White House in 1925. A photograph shows President Calvin Coolidge standing on the carpet, which is no mere juvenile effort, but a complicated, richly detailed work that would hold its own even in the largest and most ceremonial rooms.

If you can read a carpet’s cues, the plants and animals depicted on the rug may represent the Garden of Eden, which is about as far removed as possible from the rug’s origins in the horrific events of 1915, when the fracturing and senescent Ottoman Empire began a murderous campaign against its Armenian population. Between 1 million and 1.5 million people were killed or died of starvation, and others were uprooted from their homes in what has been termed the first modern and systematic genocide. Many were left orphans, including the more than 100,000 children who were assisted by the U.S.-sponsored Near East Relief organization, which helped relocate and protect the girls who wove the “orphan rug.” It was made in the town of Ghazir, now in Lebanon, as thanks for the United States’ assistance during the genocide.

There was hope that the carpet, which has been in storage for almost 20 years, might be displayed December 16 as part of a Smithsonian event that would include a book launch for Hagop Martin Deranian’s President Calvin Coolidge and the Armenian Orphan Rug. But on September 12, the Smithsonian scholar who helped organize the event canceled it, citing the White House’s decision not to loan the carpet. In a letter to two Armenian American organizations, Paul Michael Taylor, director of the institution’s Asian cultural history program, had no explanation for the White House’s refusal to allow the rug to be seen and said that efforts by the US ambassador to Armenia, John A. Heffern, to intervene had also been unavailing.

Although Taylor, Heffern and the White House curator, William G. Allman, had discussed during a January meeting the possibility of an event that might include the rug, it became clear that the rug wasn’t going to emerge from deep hiding.

“This week I spoke again with the White House curator asking if there was any indication of when a loan might be possible again but he has none,” wrote Taylor in the letter. Efforts to contact Heffern through the embassy in the Armenian capital of Yerevan were unsuccessful, and the State Department referred all questions to the White House.