By Simon Callow

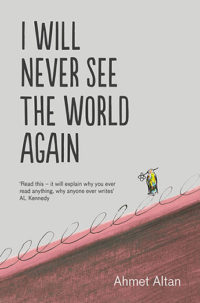

LONDON (Guardian) — To review certain books seems like an impertinence. This is one of them. It speaks for itself with such clarity, certainty and wisdom that only one thing needs to be said: read it. And then read it again. It is a short book, divided into brief chapters, some no longer than two pages, each recounting some incident from the author’s prison experience. It is wonderfully distilled, but not sententious; even in extremis, Altan never loses the limpidity and translucence, vivid with the vividness of dreams, which is characteristic of his other writing – as far as one can judge from the only other books of his available in English translation, Like a Sword Wound, the superb first volume of his Ottoman Quartet; and Endgame, a phantasmagorical crime story. Even the latter has, at the heart of all the violence, a dreamy, wide-eyed quality that seems to be quintessential Altan. To judge by I Will Never See the World Again, it has been and will be his salvation.

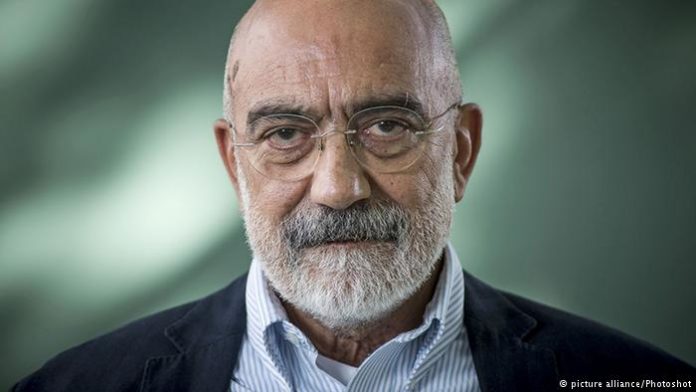

His arrest was no surprise to him. He was in the frontline. As the author of “Atakurd,” a much-read piece in Milliyet newspaper arguing for equal status for Kurds, he had, as early as 1995, received a suspended 20-month sentence, and been fined $12,000. In 2007, he founded and edited the satirical newspaper Taraf, in which, a year later, he wrote a piece called “Oh My Brother.” For this, he was charged under the draconian Article 301 of the Turkish penal code that criminalizes “denigrating Turkishness,” though not, at that time, imprisoned. Knowing how exposed his position was, he habitually carried a gun.

Dissidence is the Altan family business: Ahmet’s father Çetin, a polemical journalist, novelist, editor and MP, had been apprehended nearly half a century before by an earlier repressive regime. When the police came to get him, Altan senior offered them tea; they refused it. “It’s not a bribe,” he remarked, pleasantly. “You can drink some.” The joke didn’t go down very well. Four and a half decades later, Ahmet repeated it to the policemen who came for him; they were equally unamused. To be making jokes at all in the circumstances reveals an almost inconceivable sangfroid. He knew that there was no chance whatever of a fair trial; the sentence was a foregone conclusion.

In the car that took him to prison, the guard offered him a cigarette. “I only smoke when I am nervous,” replied Altan. He had, he said, no idea where the words came from. But they changed his life. “There are certain actions and words that are demanded by the events, the dangers and the realities that surround you. Once you refuse to play this assigned role, instead doing and saying the unexpected, reality itself is taken aback; it hits against the rebellious jetties of your mind and breaks into pieces.” This insight – “Reality could not conquer me. I conquered reality” – gave him the strength to face what followed. He saw that this capacity was an extension of his trade as a novelist: creating an alternative reality. I Will Never See the World Again is as much about writing as it is about prison, but above all it is about freedom, a freedom epitomized by the exercise of the imagination.