BERLIN — When Turkish authorities arrest German citizens they are not taking prisoners, but rather collecting hostages. What was mooted as a hypothesis months ago has been confirmed by the detention of two more individuals holding German passports.

On Thursday August 31, upon their arrival at Antalya airport a married couple were arrested and taken into custody. German consular authorities, who learned of the action through non-official channels, inquired officially and received confirmation from airport police, that the two were indeed German citizens of Turkish descent. Although no formal charges had been made, it was said that the reasons were political. The two were apparently accused of being members of the movement of Fethullah Gülen, who is officially designated a terrorist in Turkey, for his presumed role in the failed coup attempt last summer. Thus, they brought the number of politically motivated detentions of Germans in Turkey to 12.

For days, German authorities had no access to the two individuals and the foreign ministry confirmed their identities only on September 3. The same day, it was announced that a lawyer had established contact with them. On the next day, it was reported that the woman had been released. Although initially it was said that both were only German citizens, remarks by the Turkish foreign minister indicated he considered them dual citizens.

Cause Célèbre in Berlin

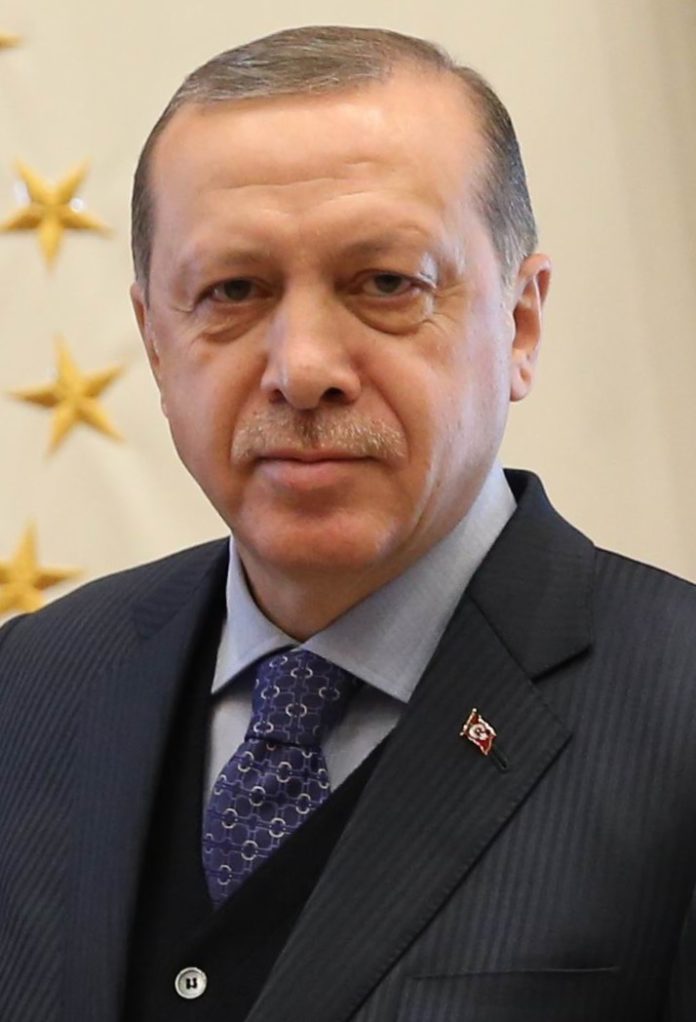

In what has become almost a ritual, political figures in Berlin denounced the arrests and fed the debate on what new measures should be pursued to pressure the government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Chancellor Angela Merkel blasted the move, saying such arrests “in most cases have no basis” in law. She called for “a determined response” and added, “Perhaps we have to rethink our Turkey policy further.” Concretely she said that talks on expanding the EU customs union were out of the question. These continuing arrests have “nothing in common with our principle of the rule of law,” she stated. Rejecting Erdogan’s earlier public appeal to German voters of Turkish background, not to cast their ballots for the CDU, SPD or Green party, Merkel said, “That is alone the decision of people in our country who have German citizenship.”

In a nationally televised debate on September 3 between Merkel and her SPD challenger, chancellor candidate Martin Schulz, viewed by 16 million people, Turkey was a central issue. Schulz promised that he, as chancellor, “would terminate talks on Turkey’s entrance into the EU,” saying that “A point has been reached where we have to end the economic relations, financial relations, customs union talks and negotiation for membership” into the EU. Merkel explained that according to regulations, the EU as a whole would have to agree to end negotiations. She stressed that her party the CDU — unlike Schulz’s SPD — had never been in favor of Turkish membership at all, and had proposed a “privileged partnership” instead. The negotiations “are non-existent, anyway” she said. The real problem is the direction Turkey is heading in; Merkel said Turkey “is distancing itself from all political manners at a breathtaking speed.” The question is: where will it all lead?