GLENDALE — Seeroon Yeretzian appeared on the art scene in Los Angeles upon graduating from the prestigious Otis/Parsons Art Institute and School of Design with a Bachelor’s Degree in Fine Arts in 1985. Numerous group and solo exhibitions followed and her art was much admired and collected. The recent “timeful: a seeroon yeretzian retrospective,” put together by her son Arno “to celebrate her while she’s still here,” showcases the various styles and phases of the artist’s career, from the earliest to the last few she painted in 2011.

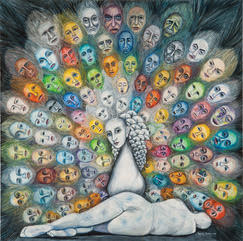

Walking into the elegant Center for Armenian Arts in Glendale on opening night was like walking into a sanctuary of dazzling colors and shapes. Even for one who has been following the artist’s work from the earliest days of her career, seeing it all so lavishly displayed in a single space was an arresting experience. The bright colors of the illustrations, the artist likes to call her “sunshine work,” blended with the darker palette of her “moonshine work,” paintings that give expression to her inner struggles and more socially relevant art. Crucified women and faceless figures trapped in webs and thorns are common themes here the artist has developed over the years.

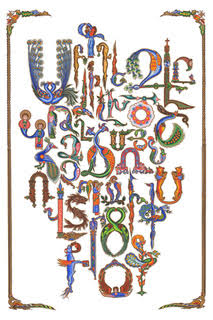

With the sunnier side of her art, Seeroon pays tribute to her identity as an Armenian. The illustrations in this phase of her creations are inspired by prehistoric Armenian rock carvings, “the oldest art known to my ancestors,” and by the great masters of the Medieval Armenian illuminated manuscripts. It was after Toros Roslin, “the greatest of them all,” that Seeroon named the Roslin Art Gallery she established in Glendale in 1995.

Roslin was a “working gallery” where the artist could often be found painting or illustrating Armenian ornate initials. Her iconic “Splendor of Aypupen,” a composition presenting the 36 letters of the Armenian alphabet replicating the Armenian Ornate Initials, has been ever popular since its creation in 1989.

“The Ornate Initials became my incurable addiction, my happiness, my medication and meditation,” writes Seeroon. Also comprising this sunshine phase are the artist’s exquisite designs of colorful peacocks, a bird that carries an important meaning in Armenian culture.

With the darker hues, the artist looks inwards. No matter how painful or humiliating, her inner truth is something Seeroon has never shied away from. The insights into the lives of the homeless and the down-on-their luck, as well as her own experiences of growing up at the Tiro refugee camp in Beirut, Lebanon — her parents and grandparents had been displaced from their ancestral lands in the 1915 Armenian Genocide — have much deepened and enriched her art.

When, because of the Civil War in Lebanon, Seeroon immigrated to “this new empire, America the beautiful,” she felt an immediate connection to the homeless and literally went into their midst, donating her time to the City of Los Angeles’s heART Project, a program that helped troubled youth to express themselves in artistic forms.

Over the years, the artist has moved away from the more direct expressions of issues in her earlier work — heads detached from their bodies symbolizing the effects of the Armenian Genocide, for example — to the subtler representations of her concerns in her later work. Even when the distorted figures and the faceless bodies that inhabit this later work are difficult to understand, they provide insight and invite reflection. My deepest regret is not having had conversations with Seeroon about her more surreal dreamlike sequences.