LOS ANGELES — Armenia’s new opposition movement is seeking a change of government in Armenia and is using a revolutionary folk song to unite nationals and the diaspora. Two words from this song have been used as the unifying element in all these protests: Zartir Lao, or Arise My Son.

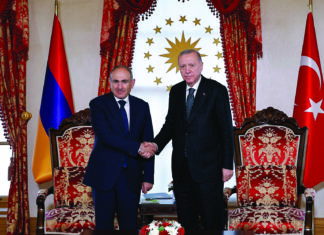

The protests started in April when Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan gave a speech that expressed Armenia’s willingness to open peace talks with Azerbaijan. Since then, the opposition has been holding protests within Armenia and the diaspora seeking his resignation.

In the past, the song served to create a sense of urgency, and as a call to arms for defense against the Turks. Today, the song has been used in pop culture and many Armenian opposition rallies, including current opposition protests. The Armenian opposition’s usage of the song has become popular not only within Armenia but during protests in the diaspora as well.

Although the use of the song has become widespread during these protests, the evolution and use of the song have shown that the focal point has drifted away from its main hero, Arabo. To understand how and why the song is being used politically today, one must first understand the historical context.

Zartir Lao: A Brief Overview