SOUTHFIELD, Mich. — Most people who learn about the Armenian Genocide are familiar with the some of the reasons that it took place and the general way in which it unfolded. The narrative that most are aware of involve various devious policies of the Ottoman government, destruction of villages and deportations to the Syrian desert, and then a miraculous end to the war and the rescue of survivors and their resettlement in various countries of the world as well as the fledgling Soviet Armenia.

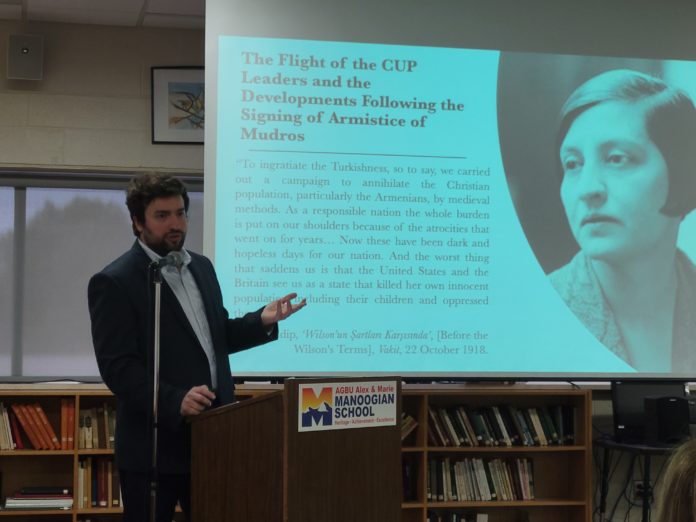

But what happened between the end of the First World War in 1918 and the beginning of the Armenian 20th century reality as we know it, in the early 1920s? Aside from the history of the First Republic, this transitional period is much less well known. Dr. Ari Şekeryan shed some light on this time period at a lecture held at the AGBU Alex and Marie Manoogian School in Southfield, on Saturday, May 14.

The lecture, entitled “The Aftermath of the Armenian Genocide: Survival and Resilience During Armistice (1918-1923)” was co-sponsored by the respective Detroit chapters of the Tekeyan Cultural Association, Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), Cultural Society of Armenians from Istanbul (CSAI), and AGBU Young Professionals.

The Transition of Armenian Constantinople

Prior to 1915, Constantinople (Istanbul) was the political, economic, and cultural center of the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire. The renaissance of Western Armenian society and culture took place in this city, which was the metropolis of the entire Middle East, starting in the mid-19th century.

After the Genocide, that all changed. Today, the Istanbul community, though still proud of its roots and holding on to what’s left, is vastly weakened. The continued maintenance of the Armenian identity and culture through the churches and schools is something to be proud of, but no one can imagine that it is anything like it was before.