Synergy from the Stress Points of Four Lifelines (Baraka, 2021), the latest in Kardash Onnig’s Baraka Projects, makes the intangible tangible. In the artist’s own words, the sensually-created carvings assembled in this handsome volume (unusually hefty for Onnig), “transcend” the subject to reach the essence of the material he was “carving,” and become a gateway to the spiritual world Kardash has spent a lifetime exploring.

These carvings are charged with an emotional force that is very much felt as well as seen. When experienced in their totality, they create a sense of wholeness and harmony in the viewer, and bring her closer than ever to Onnig’s vision of a world where love and compassion prevail. In an uncanny way, the photographs of the sculptures, taken by celebrated photographers like Arthur Cholakian, Seizi Kakizaki, Tony Kent and others, make the artist’s elusive idea of a three-dimensional consciousness accessible to the viewer. In the words of one of the 20th century’s most influential sculptors, Constantin Brancusi, Onnig’s art is “most realistic . . . What is real is not the appearance, but the idea, the essence of things.”

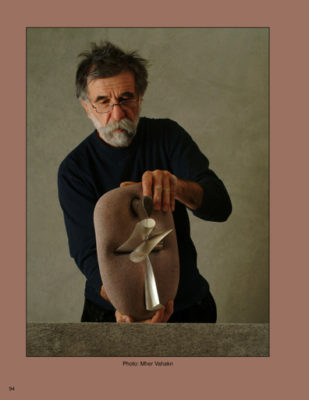

cement 8”H. Photo: Mher Vahakn

The universal has always been at the core of Kardash Onnig’s initiatives. In a 25-page-long Introduction, Kardash draws a timeline of the different stages of his evolution, which has remained amazingly focused on his vision of a three-dimensional universe that will replace the two-dimensional paradigm that has us headed for destruction through its wars and its divisions.

In project after project, Onnig experiments with the “Four Tools of Being” he invented to create a universal alphabet. Kardash adopted the principle of four, the Quaternary, as a link among cultures worldwide. Sometimes, the artist is dismissed as a madman because the world he wants to create, “a world that can be brought together by a universal alphabet,” is an “impossible” world, Yet, the artist’s ability to transform his vision into visually appealing art objects, makes his plea to bring back the spirit (Voki) to a world reduced to surfaces and to commodities relevant, and needed.

Particularly appealing, both conceptually and aesthetically, is the 1990 “Way of the Cross/Crossing Borders,” an installation of sculptures at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. The installation conveys a symbolic “crossing” of the Turkish/Armenian border by using 14 stations of the Cross as metaphors for reconciliation. In 1982, as a token of his genuine desire to reverse the destructive course of our ways, the artist changed his name to Kardash, which in Turkish means “brother.”

“This book is my tribute to others,” writes Kardash Onnig. Onnig’s vision of a “humanity with no borders” in no way contradicts his all too obvious connection to his Armenian identity, even if that connection sometimes manifests itself as rage at the lack of spiritual leaders in our present context. The artist’s is a yearning for a return to our identity as Armenians, an identity given to us by our land. For example, with his 1988 “HyeKud” initiative, Kardash tried to “re-establish a link between a lost mythical past and a stagnating contemporary culture of exile.” His 1987 “Portraits of the Dead” is a “eulogy for this homeless diaspora community.” We are dead because we are not in our motherland, notes the artist. Yet, his traveling to Turkey in 2006, that is, his literally embracing the quintessential “other,” was taken entirely out of the context of his life-long effort to help the evolution of mankind into a universal consciousness, and perceived by many as a betrayal of his Armenianness.

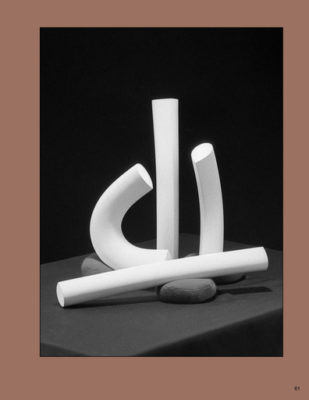

2006 bronze 16”H.