By Ronald Grigor Suny

This essay, in the form of a newspaper article reviewing reviews of a recent prizewinning book, is actually – full disclosure – written by the author of that book, the recipient of some positive reviews, and the target of some others. The voice I have chosen in this essay is of an impartial journalist, though since you the reader have now been informed of the actual author of the book and current essay, will make up your own mind about the value of this account.

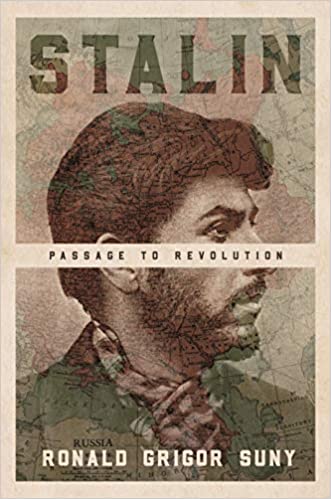

Many people may not have heard of the Deutscher Memorial Book Prize. Granted by a jury in Great Britain, the prize honors the memories of the Marxist activists and writers Isaac and Tamara Deutscher. This year’s prize was awarded to Professor Ronald Grigor Suny of the University of Michigan for his book Stalin: Passage to Revolution (Princeton University Press, 2020). This prize is given for a book which “exemplifies the best and most innovative new writing in or about the Marxist tradition.” Suny has been invited to London to give the keynote address at the annual Historical Materialism Conference in November 2022. Former prize winners include geographer David Harvey, journalist/scholar and activist Mike Davis, literary critic Terry Eagleton, and historians Eric Hobsbawm, Arno J. Mayer, Teodor Shanin, Robert Brenner, Maxime Rodinson, and Robin Blackburn, among others. Suny says he is humbled to be in a company of so many who have inspired him in his work.

The author or editor of more than twenty books and hundreds of published articles, Suny is the grandson of the Armenian composer and ethnomusicologist Grikor Mirzayan Suni (1876-1939) and the son of choral director Gurken (George) Suny (1910-1995). Appointed Alex Manoogian Professor of Modern Armenian History, Suny was the founder and first director of the Armenian Studies Program at the University of Michigan. Trained as a historian at Swarthmore College, he received his PhD in history from Columbia University. He has written books on the histories of the USSR, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the Ottoman Empire, most notably “They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else’: A History of the Armenian Genocide (Princeton, 2015). His works have been translated into Turkish, Russian, and Hungarian.

Each year the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) awards the prestigious Wayne S. Vucinich Book Prize for the most important contribution to Russian, Eurasian, and East European studies in any discipline of the humanities or social sciences published in English in the United States in the previous calendar year. In 2016 Suny won the Vucinich Prize for his book on the Armenian Genocide, and this year his book on the young Stalin won honorable mention.

Suny’s biography of Joseph Stalin from his birth to the October Revolution of 1917 is a panoramic and often chilling account of how an impoverished, idealistic youth from the provinces of tsarist Russia was transformed into a cunning and fearsome outlaw who would one day become one of the twentieth century’s most ruthless dictators. The author worked on the book for over thirty years, waiting impatiently for the Soviet archives to open. With the fall of the USSR and the independence of the Caucasian republics, Suny was able to freely mine the archives of three republics – Russia, Armenia, and Georgia – but not of another, Azerbaijan. In this book he sheds light on the least understood years of Stalin’s career, bringing to life the turbulent world in which he lived and the extraordinary historical events that shaped him. Drawing on a wealth of new archival evidence from Stalin’s early years in the Caucasus, he charts the psychological metamorphosis of the young Stalin, taking readers from his boyhood as a Georgian nationalist and romantic poet, through his harsh years of schooling, to his commitment to violent engagement in the underground movement to topple the tsarist autocracy. Stalin emerges as an ambitious climber within the Bolshevik ranks, a resourceful leader of a small terrorist band, and a writer and thinker who was deeply engaged with some of the most incendiary debates of his time. Along the way he abandoned his religious faith, instilled by his pious mother, and became a dedicated Marxist and a revolutionary outlaw, a skilled political operative within the underground Social Democratic Party, and a single-minded and ruthless rebel.