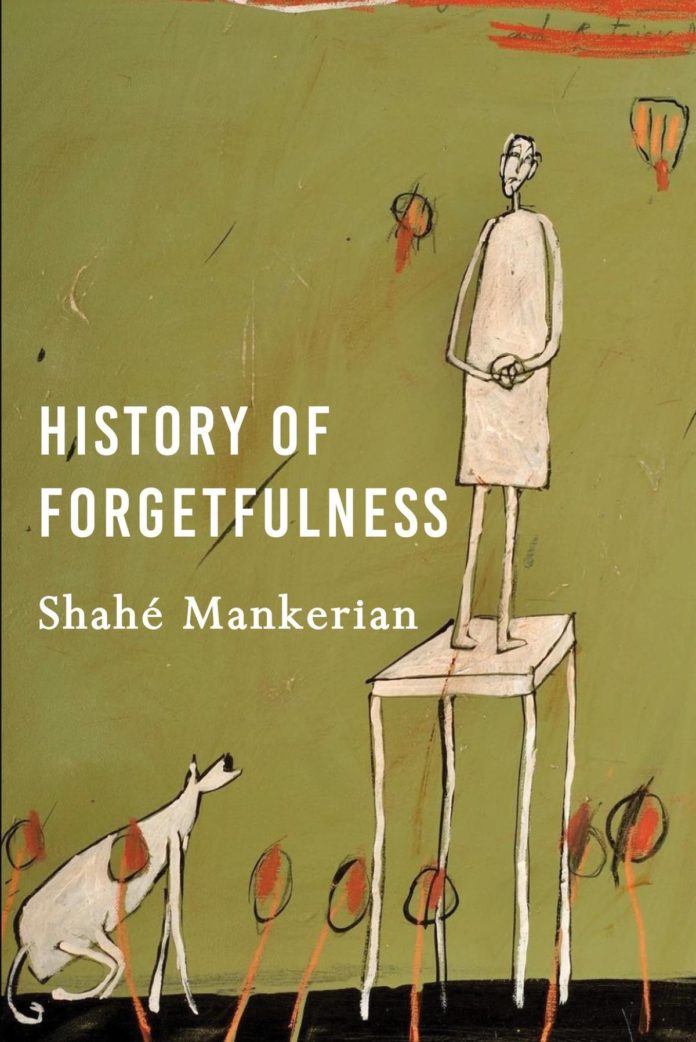

Caveat Lector: Reader Beware! Shahe Mankerian new book, History of Forgetfulness, is no walk in the park. The poet takes an honest and often devastating look at events from his childhood when the 1975 Civil War broke out in Beirut. Death is omnipresent as is human cruelty, presented on a platter for all to see and taste. Want some dressing for your pain? Some salt for your wounds?

Some more pepper perhaps for your suffering? Written in elegant and spare verse, the poems here are particularly effective because they bring home the terrifying stupidity and harm that war unleashes on its victims.

The lead poem “Educating the Son” sets the mood for what follows: “I got my schooling at the morgue:/a summer job, my mother thought,/would keep the streets out of her son.?/It was a booming business, death.” As he does elsewhere throughout these poems, Mankerian describes the topic at hand — here dressing murdered boys his own age for burial, the precision of it and also the horror — but brings it back to his own unique perspective. The poet somehow remains alive and reminds the reader that he is still his mother’s son, one who needs her love, especially given the wartime conditions:

“Would she remember that I was

her only son and that I cleaned