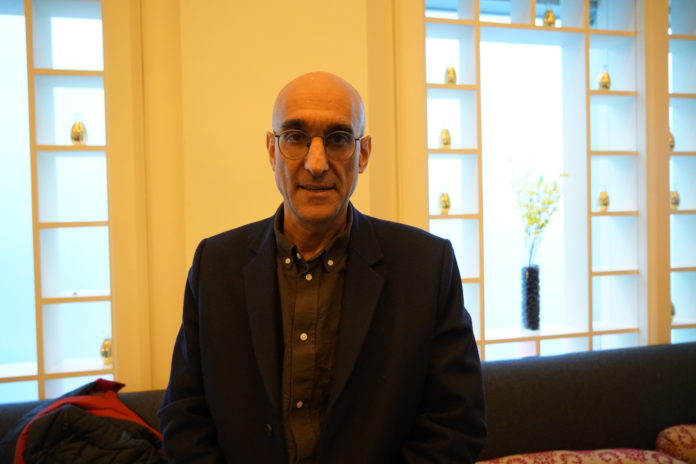

BOSTON — If you see him on the street in Boston, 54-year-old Thomas Catena may not seem different from any other guy. But Dr. Tom Catena is no ordinary person. He was chosen by Time magazine in 2015 as one of the 100 most influential people in the world. He has exerted extraordinary efforts to provide medical assistance to people in need in Africa and is an inspiring role model for those who wish to do humanitarian work. In December 2018, he was named as chairman of the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative. As such, he had come to Boston as part of an outreach tour at the end of January 2019, with several university talks and meetings.

Catena grew up in Amsterdam, a town in upstate New York, as the fifth of seven siblings. After graduating Brown University, he went to medical school at Duke University on a US Navy scholarship. After his internship he served for four years as a flight surgeon for the Navy. Although he did his military service to finance his education, he ended up liking the sense of purpose and community and if he had not wanted to work in the mission field in Africa, he said that he would have stayed longer.

He said he always liked reading about other societies and cultures as a youth, but as a Catholic, he felt a calling to do missionary work when he was in college. He pointed out that having four older brothers already married with children made it easier for his parents to support his doing this work, no longer feeling the need to push him for grandchildren.

Catena did several short medical mission trips in 1997 and 1998, and after completing his residency in 1999, worked in Kenya with the Catholic Medical Missionary Board (CMMB) as a missionary doctor until 2007. He then helped found the Mother of Mercy Hospital in the village of Gidel in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan in 2008. He has been the only doctor permanently based in this region of South Kordofan, serving as many as 750,000 people, and remained there after fighting broke out between the Khartoum-based government and the Nuba people several years later, in what many call a campaign of ethnic cleansing. Patients trekked there for all types of diseases and medical problems, to which were added war and famine victims.

Already isolated due to its geography, the Nuba region became even more difficult of access for international humanitarian organizations during the fighting and a blockade by the Sudanese government. Fortunately, the conflict has been quiet for a year and a half. Catena explained that the biggest problem for access now is that the roads are terrible. In the dry season, it would take six hours to make it from the hospital to beyond the mountains, but during the rainy season from May to the end of October the roads turn to mud and it is tricky to get out due to flooding.

Due to lack of resources, deprived of most of the tools of modern technology, Catena has had to improvise or use outmoded forms of treatment. Often working around the clock in extremely difficult situations, he has saved many lives and is locally revered by Christian and Muslim alike according to most accounts. New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof reported a few years ago in a column about him titled “‘He’s Jesus Christ’” (https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/28/opinion/sunday/nicholas-kristof-hes-jesus-christ.html) that he did all this on a salary of only $350 a month, with no pension or health insurance.