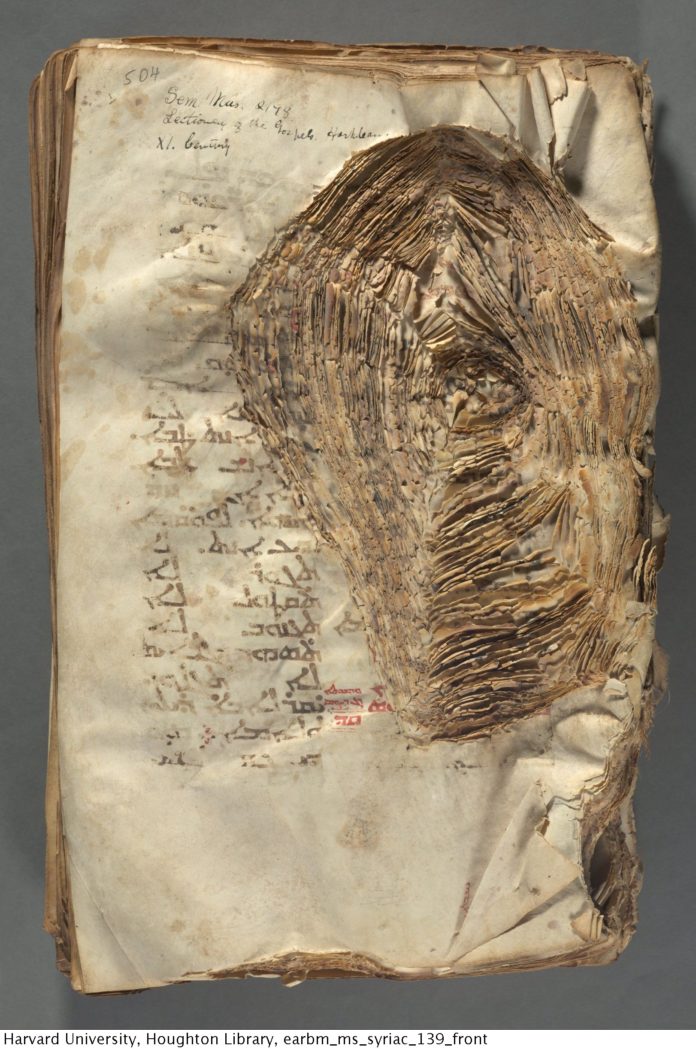

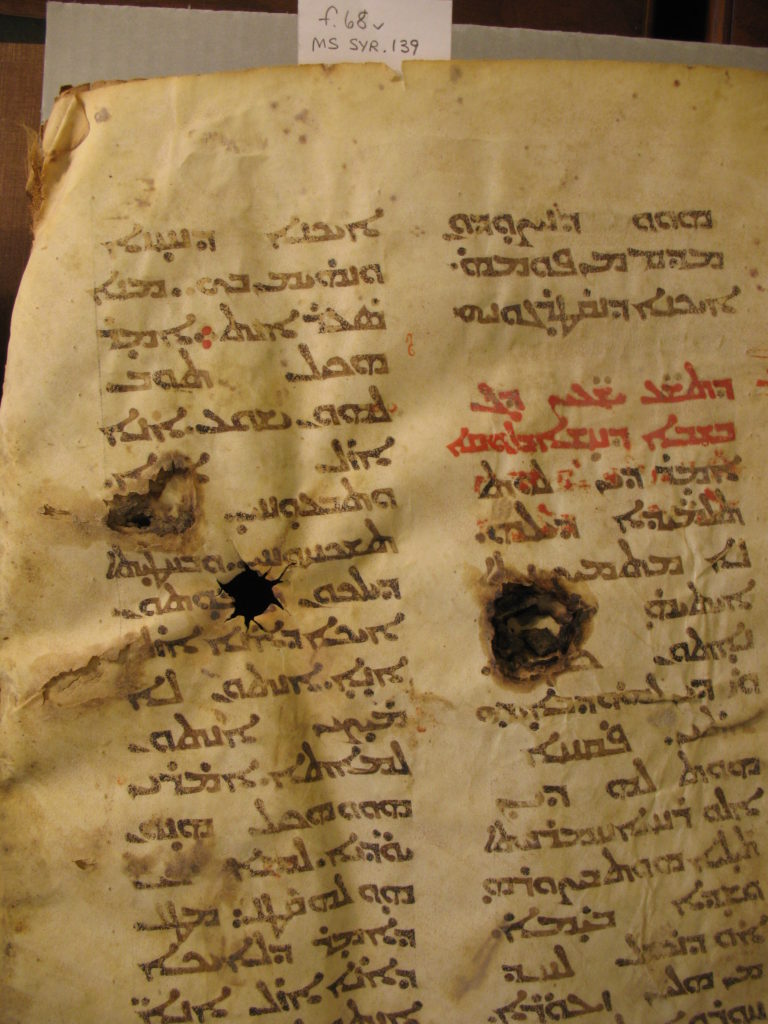

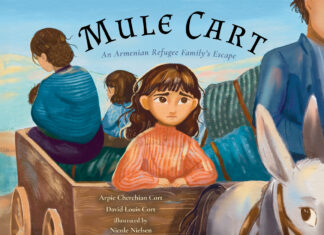

MEDFORD, Mass. – On the evening of April 18, the Darakjian-Jafarian Chair in Armenian History, the Department of History, the Armenian Club, the Executive Administrative Dean and the Armenian Club, all part of Tufts University, together with the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR), sponsored a commemoration of the Armenian Genocide at Goddard Chapel at Tufts with Dr. Sylvie L. Merian delivering an illustrated talk dramatically titled “Slash and Burn: How Two Manuscripts Survived a Violent Past.”

Professor Ina Baghdiantz McCabe, holder of the Darakjian-Jafarian Chair, thanked the donors supporting the commemoration, including Joyce Barsam, and dedicated the event to Merian’s great-grandfather, Hagop Babigian, a lawyer and member of the Ottoman Parliament. Babigian, sent to Cilicia to investigate the 1909 massacres of Armenians, wrote a report but mysteriously died before able to present it. Foul play was suspected.

Baghdiantz McCabe introduced Merian, who received her PhD in Armenian Studies from Columbia University’s Department of Middle East Languages and Cultures, where the two studied together with Prof. Nina Garsoïan. Merian has published and lectured internationally on Armenian codicology, bookbinding, silverwork, manuscript illumination, and the history of the book.

She is one of the few specialists writing on Armenian manuscripts, bindings and books in this continent. Merian is currently Reader Services Librarian at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City and at present is preparing entries for the catalogue of the upcoming Metropolitan Museum of Art Armenian exhibition. Baghdiantz McCabe provided some background to the work of Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide.

Merian expressed her gratitude to the organizers and sponsors of the evening, as well as the Houghton Library of Harvard University for the Katherine F. Pantzer Jr. Fellowship in Descriptive Bibliography and the help of its staff for her research. She recognized in the audience Nancy Keeler, who along with her late sister Ester Seferian shared information about one of the manuscripts she was going to speak about.

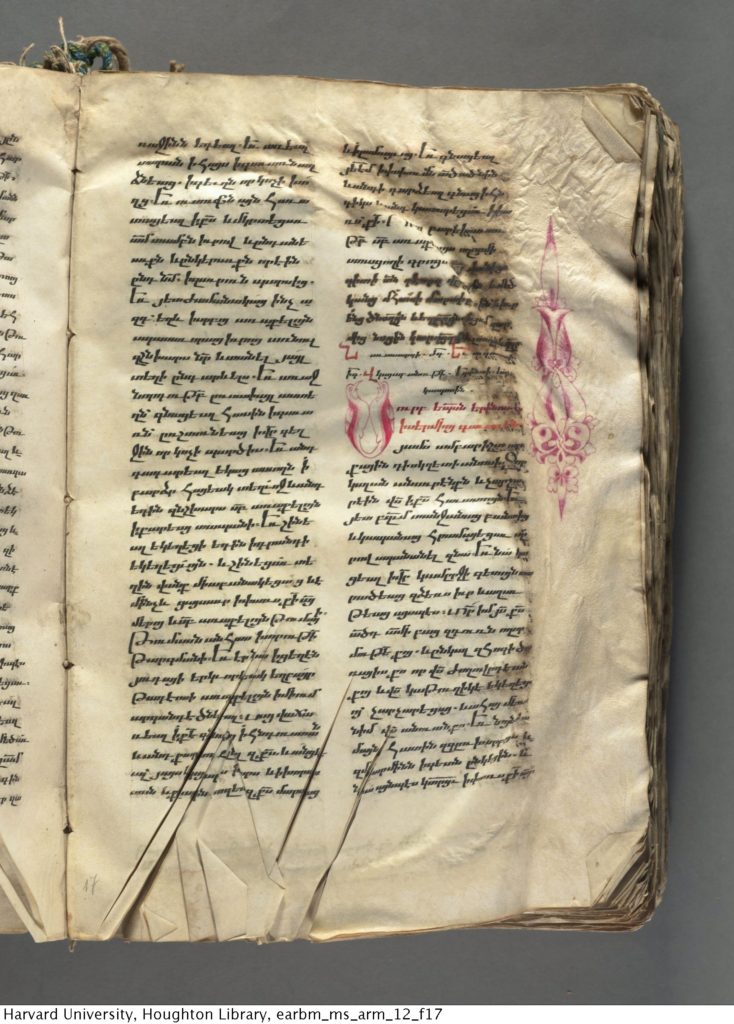

Merian delivered a very accessible talk accompanied with illustrations in which she explained all the academic terms used. She started by explaining that a manuscript is a handwritten book produced without a printing press by a highly trained scribe, often with decorations by an artist. It can be on paper or parchment, which is made from specially prepared animal skin, stronger than paper but more sensitive to changes in temperature and humidity. Most Armenian manuscripts at their conclusion, she said, contain colophons (hishadagaran in Armenian), inscriptions usually written by the scribe which include where and when the manuscript was completed, the names of everyone who helped produce it, the name of the sponsors who commissioned and paid for the work, historical information and detailed information about the scribe’s own family.