By Philippe Raffi Kalfayan

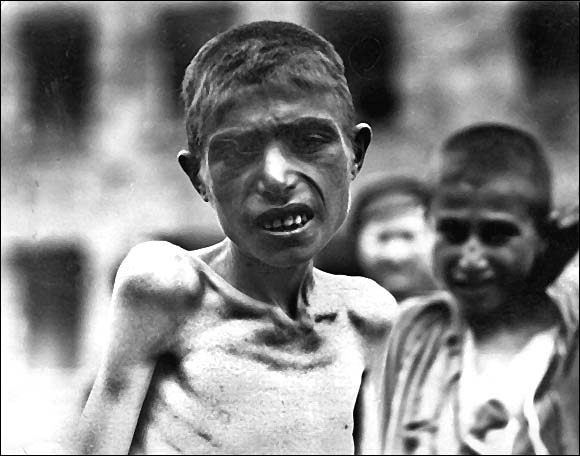

In the first place, the author wishes to pay tribute to the historians of the Armenian Genocide, from the pioneers to those who work today on the Ottoman archives. The latter have been accessible for about 10 years, and their contents are undermining the official Turkish version of the events of 1915-1923.

Typical of all mass state crimes, documentation and truth emerge at a later point. Historians therefore still have much work to do in analyzing the documents. However, room should have been made for lawyers, because the more time passes, the fewer solutions the law offers for a judicial response to the events. It is worth remembering that “historical truth” is not “judicial truth” and vice versa.

The author submits that the recognition of the Armenian Genocide by Turkey will become possible when its domestic politics will enable it (Armenia’s first president, Levon Ter-Petrosian, was arguing that the recognition matter is not ours but Turkey’s). As long as Turkey is ruled by a nationalist and religious discriminatory ideology, which is at the very foundation of its republic, neither resolution nor declaration from a third country will be able to put an end to the official policy of genocide denial. The Armenian side is no less nationalistic, the official doctrine of the government, espoused by the Armenian lobbies in the diaspora, is based on the sole process of political recognition of the genocide at the international level. President Armen Sarkisian, who was just sworn in, said that recognition of the genocide is not an end in itself. The author agrees with this assertion, but formulated as such, it is insufficient, and in this respect contrary to the need of justice expressed by each Armenian.

In 2015 I wrote about the political stalemate that constituted both the “Pan-Armenian” Declaration of January 29, 2015 and the dogmatic fight around the use of the word genocide, but, above all, about the fact that the compensation due for the massive and serious violations of human rights and humanitarian law by the Ottoman Empire does not depend upon the criminal characterization of the crimes committed.