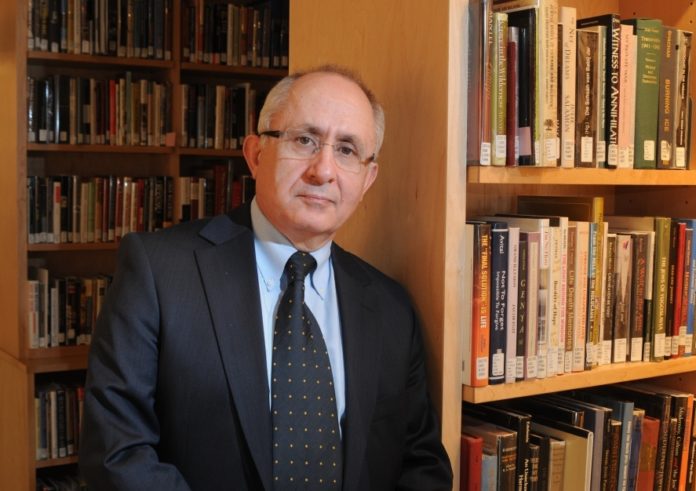

By Alin K. Gregorian

Mirror-Spectator Staff

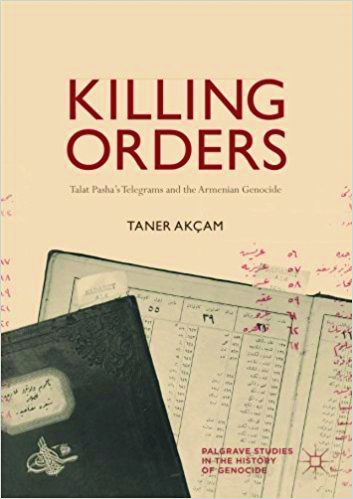

WORCESTER — Prof. Taner Akçam has been at the forefront of finding evidence confirming the Armenian Genocide and the role of the Ottoman central government in the murders for decades. His latest book, Killing Orders: Talat Pasha’s Telegrams and the Armenian Genocide, is the latest volley he has launched to bring down the curtain of denial of the Turkish government.

The book, published this week by Palgrave Macmillian, is an expanded with additional two new chapters available only in English-language translation of his book on Naim Bey, which was originally published in Turkish last year.

In it, Akçam literally shows the orders from the central government to exterminate Armenians in various parts of the country. Many have referred to the book’s explosive content which once and for all shows that not only the genocide happened but that it was done on orders of the central government, as an “earthquake” in the field of Armenian Genocide studies.