By Edmond Y. Azadian

May 2018 will be a watershed in Armenian history because it will mark the centennial of the revival of Armenian statehood. During the months leading up to that benchmark, the news media and political groups are positioning themselves to share in or to own the limelight.

There are discussions about the events leading to the formation of the First Republic in 1918. There are also proprietary claims on the leadership who contributed to the birth of the First Republic. Yet, there is little talk about the demise of the republic or the status and historic value of its successor, Soviet Armenia, which shaped the world view of generations of Armenians, for better or worse.

The Armenian government, currently in a coalition with the ARF and eager to carry its own political agenda, is on the path of a pragmatic policy, not too interested in upholding the historic truth. Everything seems to be up for grabs.

We are not certain if Armenia and the diaspora combined are celebrating the historic victories at Sardarabad, Ghara Kilisa and Bash Aparan or the inception of the first period of statehood after six centuries of statelessness by Armenians.

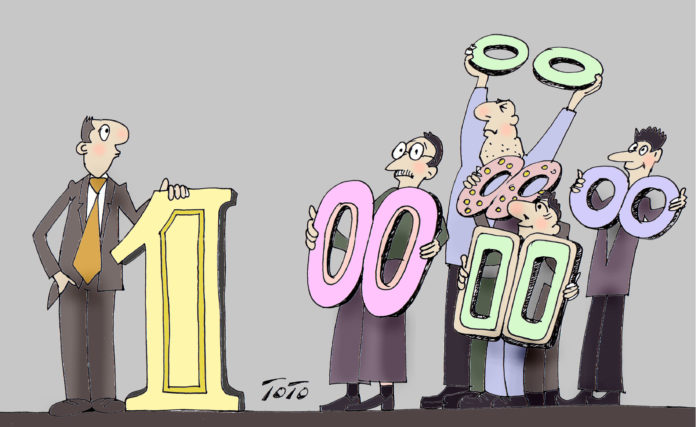

Since all the above battles were fought through popular participation and since the ensuing republic was valued by all the surviving Armenians from the Genocide, it would make more sense to celebrate one hundred years of statehood, irrespective of our views of who lost the First Republic, what percentage of sovereignty the Soviet Armenian Republic enjoyed and how post-Soviet independent Armenia is performing.