By Joseph Dagdigian

By Joseph Dagdigian

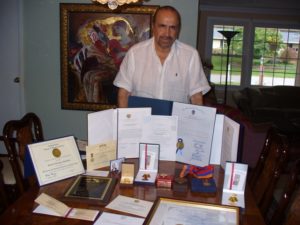

CHELMSFORD, Mass. — Daniel Varujan Hejinian is well known for his billboards around the state demanding recognition of the Armenian Genocide. His art focuses on Genocide recognition, human rights and democracy. His paintings proclaim his thanks for the freedom of his adopted country, the United States, while demanding that the US acknowledge the Genocide perpetrated upon his ancestral homeland, Armenia. He has received many acclamations from organizations in the United States and from the Armenian government.

This interview was conducted at his home in Chelmsford.

Joseph Dagdigian: Varujan, please briefly describe your art and your artistic style.

Varujan: The public knows my work more than they know me. As an artist my goal is to create meaningful and beautiful paintings.

I was first inspired by the romantic artist Eugene Delacroix, and then Rembrandt, Dali, and Cezanne. They have undoubtedly influenced my art; the curvilinear quality and occasional dark outlines, the division of colors, and the vibrancy of colored patterns. The compositions are often a combination of the medieval and the surreal. The technique may be traditional, but the result is a wholly unique signature style.