By Harry N. Mazadoorian

HARTFORD, Conn. — My parents were both survivors of the Armenian Genocide of 1915, having undergone unimaginable hardships and deprivations. As were so many of the victims, they had been uprooted and displaced time and again, with very few family keepsakes, photographs or possessions to remind them of the precious times before the brutalities began.

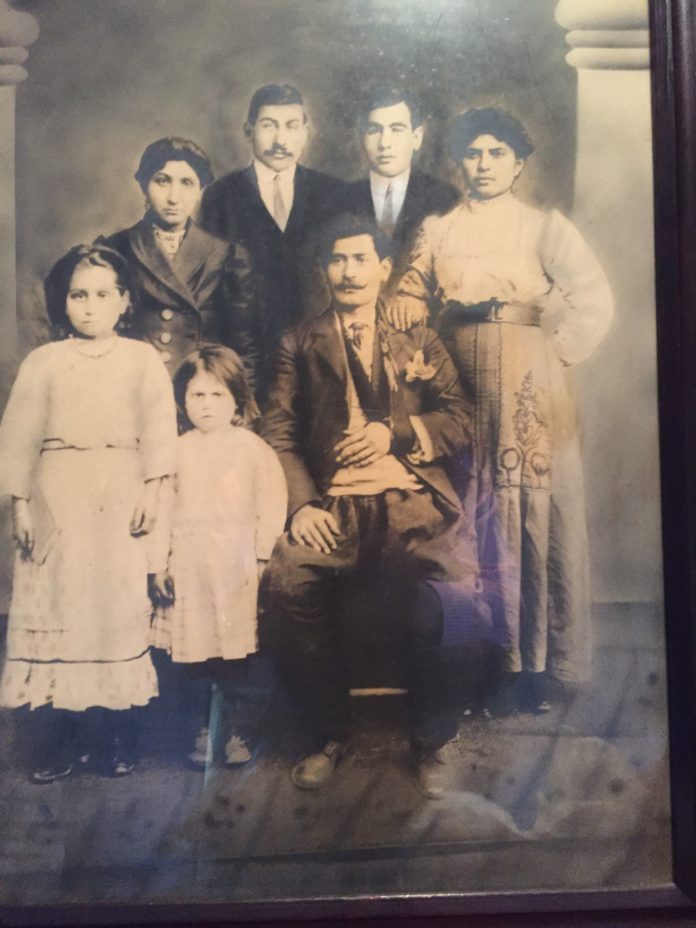

One of the few physical reminders which survived the turmoil and upheaval is a portrait photo of my mother’s family taken sometime in 1914 in the province of Kharpert, where both my parents’ families lived. (My mother was from the Kharpert village of Yegheki and my father from the village of Ichme.)

This particular portrait was taken by a professional photographer in Mezre. It was intended to be sent to my mother’s father Haroutiun ( nicknamed Dado) Aharonian and his younger brother Karekin, who had traveled to the United States to earn money and improve their economic condition before returning to Kharpert. A third brother Aharon had also been with them, but had returned home prior to the Genocide. The photo shows my grandmother Loosig standing behind her two daughters Sarah and younger sister Yegsa, my mother. Also in the photo is my mother’s horyeghpayr ( paternal uncle) Aharon, who had returned from America, and his wife Hazervart.

A close examination of the photo tells the viewer a great deal about the subjects and the times. My grandmother Loosig has a courageous but stoic and mournful look about her revealing her concern about the increasingly difficult times being experienced by her family and the absence of her husband Dado, still in the United States. Aharon’s attire speaks to his return from America. The western influence also is implied by the fact that none of the women in the photograph have their heads or faces covered. Aharon’s left arm is in a sling following an injury he sustained leaping from rooftop to rooftop evading a Turkish home inspection. His expression appears to be one of quiet defiance and pride. Seated, among four standing women, he conveys an air of authority as the acting patriarch of the family, while his two brothers still toil in the factories of New Britain Conn., thousands of miles away. My mother’s older sister Sarah has a benign expression on her face, whereas my mother’s face discloses an unhappiness and anger, which our family stories tell us is from a punishment meted out to her by her uncle just prior to the photograph being taken.

But in addition to the original portrait photo, there was another version of this wonderful picture. The second, photo, however, contained the additional images of my grandfather Dado and his brother, Karekin, apparently superimposed between Loosig and Hazevart: an early example of photoshopping. In addition to the two men being inserted into the photo, the quality of the photo has been enhanced, giving it greater clarity and definition. The images of the two men, who were still in America at the time the first photo was taken, appears to be from a photography studio photo the men took and apparently sent to the family in Yegheki. While I do not have the forensic wherewithal to determine exactly when or where the images were superimposed, the more central question is why the family went through the effort to create it. The purpose of the second photo, whatever its provenance, is unequivocally clear: a desire to remember – and to actually see-all members of the family together even though that was not physically possible. It was an anticipation of a future reunion which they hoped would take place.