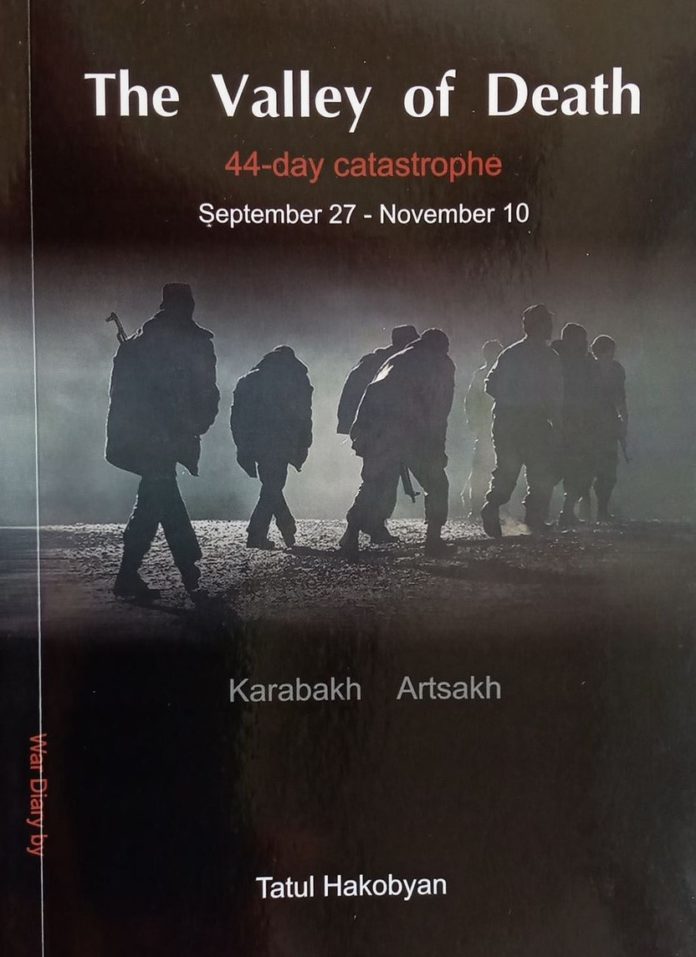

There are still many mysteries about what happened during the 2020 44-day Karabakh war, though the results of the war are clear. The collective mind of the Armenians is still digesting the significance and impact of the war and the defeat, with differing views often expressed in severe fashion. Journalist Tatul Hakobyan wrote frequently during and after the war from the front lines in the Armenian media, and has given many public talks, including in the United States, after the war. His collected writings on this topic were published first in Armenian, and then, last year, in English under the title The Valley of Death: 44-Day Catastrophe, September 27-November 10. War Diary (Yerevan: Lusakn Publishing House, 2021). Arsen Kharatyan, founder of Aliq Media, translated the majority of the 335-page book from Armenian into English, with a small number of pieces having been translated by Vahe H. Apelian.

This volume is not a monographic study. Instead, it is an anthology of news articles, interviews and opinion pieces by Hakobyan, who after graduating Yerevan State University’s Department of Journalism and the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs in Tbilisi, wrote as a correspondent for the Armenian and diasporan newspapers Ankakhutyun (1991-95), Yerkir (1998-2000), Azg (2000-2005), Aztag (2005-2016) and Armenian Reporter (2008-9), a columnist or political observer for the Radiolur news program of the Public Radio of Armenia (2004-2008), the online Aliq Media (currently), and CivilNet online television (for the Civiltas Foundation) (2009-2022). Since 2014, he has been a coordinator of the Ani Armenian Research Center.

Kharatyan in his preface notes that “This work shows how the official information provided to the public by Armenian and Karabakh officials during the war misled and confused our nation, when the realities on the ground were far worse from [sic] what we were being told.” In his “Author’s Note,” Hakobyan writes that he was unable to publish many of his reports in real time as a result of martial law in Armenia, especially as they contradicted the “official line” of the government. He published them only after the November 10, 2020 trilateral ceasefire agreement signed by Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia.

Around half the articles in the book are about the developments of the war, and the other half provide historical information and broader context. A number of pieces pay special attention to the 2016 April four-day war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and the newest pieces cover developments up through February 2021. The articles are presented in reverse chronological order, starting with the most recent. Five texts of negotiation proposals and agreements on Karabakh are appended at the end of the volume.

Hakobyan raises important questions on many topics. Most pressingly, what will the long-term fate of the population and remaining territories be of the Artsakh Republic? He finds three possible ways to ensure the security of the Armenian population there. The Russian peacekeeping force might stay for 50 instead of 5 years, and make Karabakh a Russian territory, as it was in the 19th century. Armenia may become powerful enough to provide Karabakh with security guarantees. An agreement might also be reached between Armenia and Azerbaijan giving Karabakh an in-between ambiguous status which allows it de facto independence.

If Azerbaijan fully controls the territory, Hakobyan can only picture a nightmare scenario of depopulation or massacre of the local Armenians. He mentions the possibility of Armenia regaining full control of Artsakh, and without directly commenting on its likelihood, notes that Armenia is unable to defend its own borders at present.