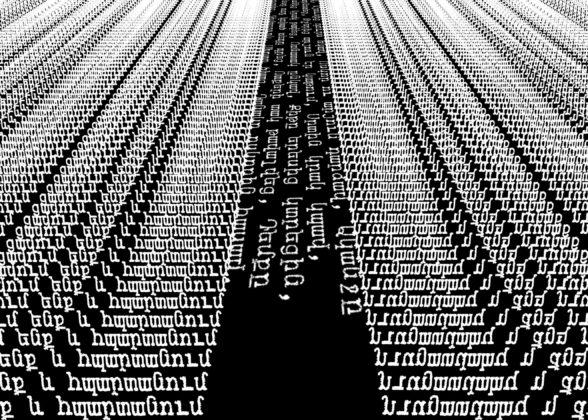

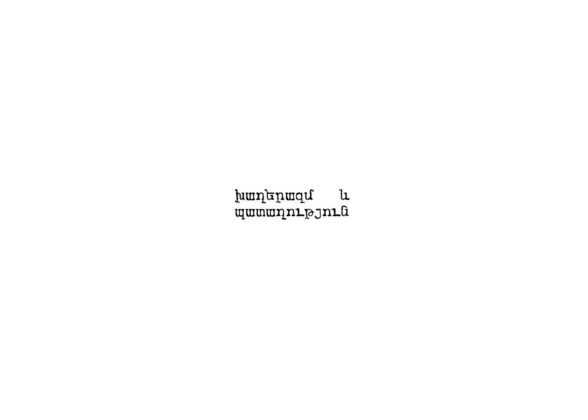

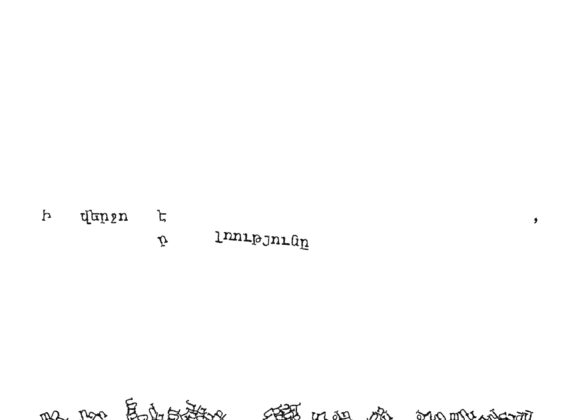

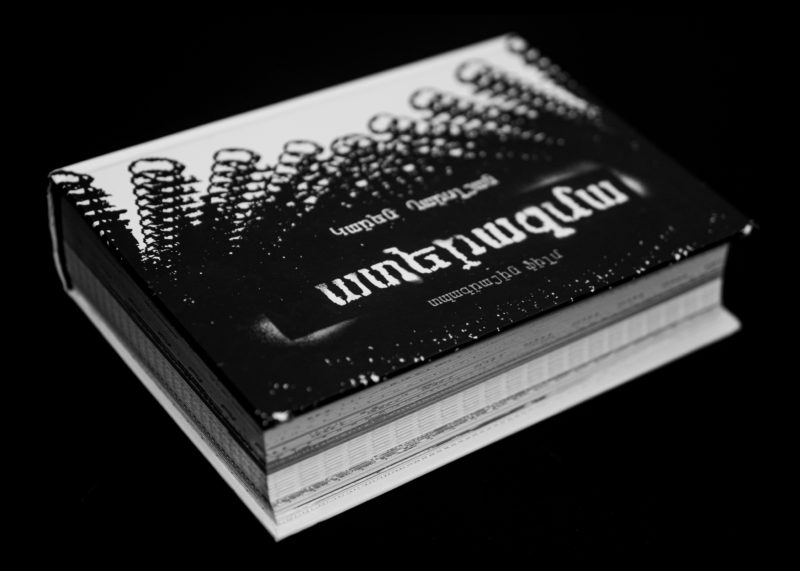

Is it a book? A work of art? Book art? Or perhaps an art book? Karén Karslyan’s 2020 tome goes by the name of Aterazma, a clever play on words: transliterated into Western Armenian, Baderazm, meaning war; the verb adel to hate and yeraz, dream. Part artwork, part fiction, Aterazma limns the borders between both disciplines. In its close to 500 pages, Karslyan aligns letters on the page like soldiers going to war: a prisoner on one page becomes liberated towards the end, a message of hope in an otherwise deadly serious book presented in the guise of a ludic exercise. Commenting on this constant play on meanings and words, Karslyan notes that:

The ludic effect is more of a byproduct of the initial concept for the book. It is an aftermath of imagining the language in ruins, when devastated by the reports of the first casualties flooding the news outlets and social media, following the surprise Azeri offensive on April 2, 2016. When I suddenly noticed the word ‘yeraz’ hidden in plain sight inside the word ‘paterazm,’ I started taking more and more words apart. And soon the whole book turned into an operating table, a lingual one. This ludus can be viewed as an alternative rhetoric strategy or as a key auxiliary to the four major rhetoric appeals. We are, after all, homo ludens.

Aterazma obviously presents a dystopic world to readers, but one “that yearns to be refuted” as the author notes in a recent conversation. For all its deconstruction of traditional norms of both art and fiction, Karslyan’s work remains binary in the sense that it opposes certain themes such as war and peace; heroism and cowardice, nationalism and individualism; patriotism and cosmopolitanism, inevitability of war, the limitations of language when it comes to expressing the horrors of war.

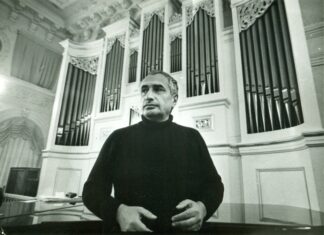

Born and raised in Yerevan, Karslyan obtained his PhD in English from the Brusov State Linguistic University with a dissertation on James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake and Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy; more deconstructable authors would be hard to find.

The author/artist/animator then moved to the US at the age of 25 and now lives in Chicago where he mainly writes poetry and produces artwork in different media. Of the differences between living in Armenia and in the diaspora, Karslyan has much to say. He brands Armenia an “extrovert’s paradise,” though he himself is rather introverted but also notes “putrid manifestations of patriarchal values, toxic masculinity, overall intolerance toward new or different stuff, and sense of ethnic superiority.” In the end, the Armenian language is what bonds him to his homeland: “Armenian literature, art, cinema, and music are my building blocks. I do my best not to sever my ties with Armenia. I visit it almost every year, and during the 16 years outside Armenia, I have continued writing and publishing in Armenian.”

As for the United States, he notes that despite the fact that he bears a woman’s name and one that is used as a derogatory term for “a fussy middle-aged woman” he has never encountered any derision — a telling indicator of American society’s tolerance. Or as he notes: “I bet I wouldn’t fare as well, had I been a bearded Anahit in Armenia.”

Karslyan dreamt of being the Walt Disney of Armenia. The war interrupted this dream to a certain extent, and Karslyan turned towards literature. That being the case, the book also includes elements of interactive theater and kinetic typography, etc. One of the may fascinating aspects of Aterazma lies in the fact that it can be read on many levels: a general anti-war tract, an artistic guidepost towards peace, a look at violence in human society on a general level, finally an almost interactive play between literature and art, letters and drawing, signs and referents. Given the recent 44-Day War and Armenian history in general, the book must also be read as a comment on relations between Armenians and Turks/Tatars and the continuing centuries-long conflict between these peoples. The second half of Aterazma is titled “Deleted Scenes” — this is where reconciliation, peace and friendship between Armenians and Azerbaijanis are imagined: “By putting these utopian scenes under Deleted Scenes, I wanted to emphasize that our nations have discarded this possibility at least for a very long time.”

Karslyan dreamt of being the Walt Disney of Armenia. The war interrupted this dream to a certain extent, and Karslyan turned towards literature. That being the case, the book also includes elements of interactive theater and kinetic typography, etc. One of the may fascinating aspects of Aterazma lies in the fact that it can be read on many levels: a general anti-war tract, an artistic guidepost towards peace, a look at violence in human society on a general level, finally an almost interactive play between literature and art, letters and drawing, signs and referents. Given the recent 44-Day War and Armenian history in general, the book must also be read as a comment on relations between Armenians and Turks/Tatars and the continuing centuries-long conflict between these peoples. The second half of Aterazma is titled “Deleted Scenes” — this is where reconciliation, peace and friendship between Armenians and Azerbaijanis are imagined: “By putting these utopian scenes under Deleted Scenes, I wanted to emphasize that our nations have discarded this possibility at least for a very long time.”