YEREVAN — Ambiguity lends a special quality to art. Not ambiguity as attempted deception, but as an invitation to explore what is unstated, merely hinted, or lends itself to multiple, even contradictory interpretations. An exhibition that opened on November 9 at the Yerevan Modern Art Museum is a perfect example. Guy Ghazanchyan is the artist and the title of the exhibition is “ԱԿԱՆատես” [Akanatehs], which contains a double meaning, through a play on words. In Armenian, this means “Witness” but if you isolate the first four letters, the word means “land mine.” Then a connecting vowel “ա” comes, followed by “տես” which is a word root meaning “see,” thus the title also implies “someone who saw the land mine.”

The exhibition is akin to a project, an action, an act of dedication. The concept, in the words of the artist, is depicted as follows: “А moment is like a verge, like a deafening sudden reality that questions the here and now. A frightening border between the Real and the Unreal, an attempt to stop time, to hear an unasked question, to stand at a dividing line, to see your own self and to realize the impossibility of accepting a given.”

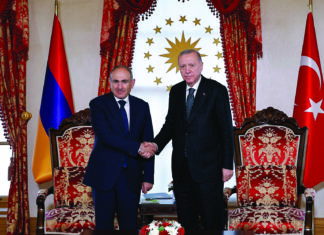

The day of the opening marked the first anniversary of the trilateral ceasefire agreement after the war in Artsakh, and the subsequent entry of Russian peacekeeping forces into the conflict zone. There are 44 items on display — paintings, an animation and a sculpture. The number of pieces exhibited was purely arbitrary; in fact, some works were removed during the show and, as all works appear under one title, no one even counted them. The first to take note of the number were the journalists. The 1st Public TV channel of Armenia, the country’s main public channel, carried a report on November 9, the day the exhibition opened, in the evening news. Up to that time no one (not even the artist) had pointed out the number of exhibited paintings. Everyone seemed surprised by such a coincidence: 44 paintings and the 44-day war.

Guy Ghazanchyan had started work on the project actually at the beginning of 2020, and, on reflection, thinks that he may not himself have fully realized what was emerging. Certain features of his earlier works, female images, aerial light compositions had vanished and given way to new concepts. It is hard to tell what triggered this change, but as the subsequent tragic developments unfolded, he followed the road chartered with new strength.

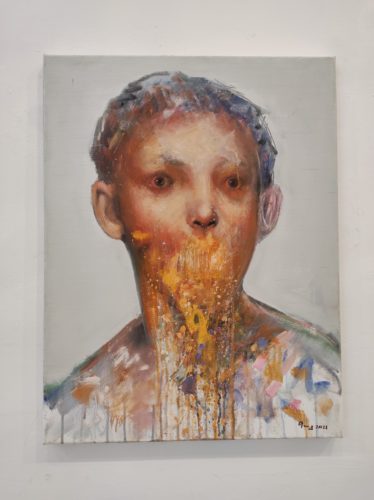

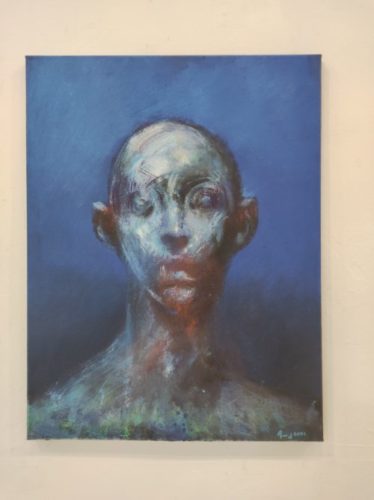

Portraits – of Whom?

With every new painting a new, horrifying image of a young man was born, with the frozen expression of an unanswered question on his face. The question, that, in Guy’s view, the beholder has to hear himself. We move from one portrait to the next, and despite the blurred, almost amorphous shape of each, we know that each is a distinct human being, an irreplaceable individual.