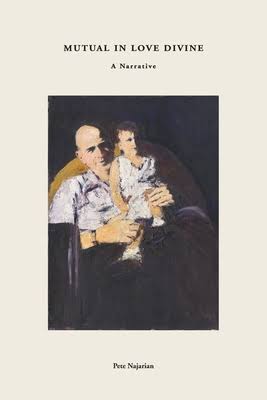

When he switches from writing to painting, “You turned from one no-money work to another no-money work, and now no woman will want you and you will never have a family,” says Zaruhi Najarian to her son Pete (also the narrator) in the episode titled “The No Money Work,” in Pete Najarian’s recently published Mutual in Love Divine (Regent Press, 2021). The mother knows that her son needs connections to wife and family and friends to combat his loneliness and his fears.

Mutual in Love Divine is a narrative comprising 16 episodes around the theme of sickness and death.

The episodes start with the narrator as a little boy who would light a candle and pray for his crippled father to heal, and end with the “so many deaths” of the 1988 earthquake in Armenia, a fitting finale to the countless deaths of “the nightmare of history.”

Najarian’s vivid account of the desperate search by the rescue teams for bodies among the twisted steel cables and the concrete slabs of the collapsed buildings — “maybe there was another baby buried alive” — evokes the horrors of the death march of which his crippled father and his mother with the wooden ladle — ever-present throughout the narrative — are survivors.

Najarian’s description of the chaos, as the volunteers and the rescue teams’ shovel and haul and dig for dead bodies in the mounds, makes us “feel death and taste it and know it.” The corpses covered by sheets at the side of the city square and the coffins, “only a few yards away,” make death palpable.