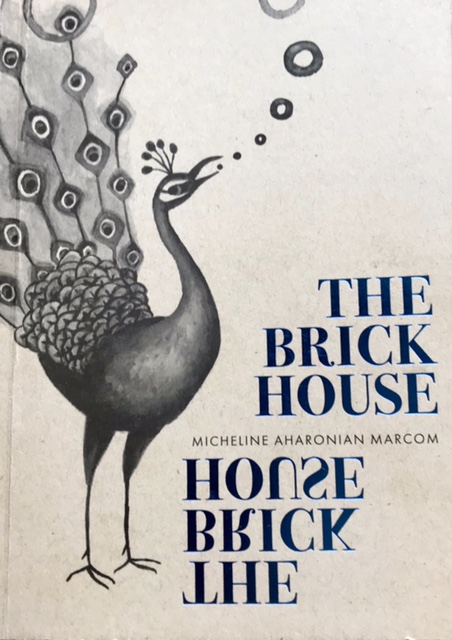

LOS ANGELES — Prior to reading Micheline Aharonian Marcom’s The Brick House (Awst Press, 2017), a novel that explores the horrors of the modern city through the irrational world of dreams, I had stumbled upon Marcom’s latest novel, The New American (Simon and Schuster, 2020), which, with its more conventional narrative structure and recognizable details of the phenomenal world outside, I had found to be perhaps a trifle too much on the surface for Marcom. I had read Aharonian’s trilogy of novels dealing with the Armenian Genocide and its aftermath, as they were coming out, and remember being seduced by Marcom’s depiction of the internal landscape of her characters and also by her deviations from ordinary discourse to shake the reader into the significance of the crime. Discovering The Brick House, which also journeys into the interiority of her characters to make sense of their lives, was like rediscovering Marcom.

The world of The Brick House is a strange world with a logic of its own. A dilapidated, neglected brick house sits on top of a hill on a moor in a remote peninsula in an unspecified location. (The closest we get to the specifics of its location is North America and the Pacific Ocean.) The caretaker of the house is old and indifferent. The furniture in the seven rooms lining a long corridor painted in a “foul green paint” is tattered, unwelcoming. “When one speaks of the brick house, one must also speak of the light that does not shine. The electric lights are lighted but they do not illuminate the darkness: the foul green paint extinguishes the light; the closets extinguish the light; the despair and loneliness, the closed heart of the traveler who visits with his sombering fear,” writes Marcom.

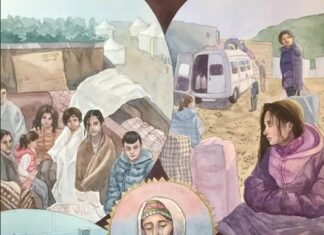

Travelers from the city are lured to the brick house through a chance encounter with a stranger, who approaches them in a supermarket and speaks to them of a house on the moor, where they are invited to spend a night, to “die,” and to return restored. The visitors to the house are lonely, fearful and panicky, plagued by feelings of “dissolution and separateness.” They are “city men” come to get away from the pollution of their “noisy and busy” city lives, the banalities of their conversations about “cruel bosses and the rising cost of goods and petrol,” and the horror of “an agreed-upon vision of the world” they share with their spouses. These desperate souls are described as pilgrims on a pilgrimage to an unreachable end.

Something is clearly amiss in “the new desert city,” and Marcom is determined to understand “the cause of causes” that created the “unrivered,” “unforested” “concrete immensity.” There are hundreds of colorful vehicles on the “huge concrete overpasses,” but “no animal or plant life” one can see. “The noise from the cars and the noises of the helicopters and aeroplanes in the machined sky above her [the unidentified traveler] fill the air with their din and strip her naked (for although her body remains clothed, her soul is bared, she thinks, with this onslaught to her ear)” (italics mine). Citizens in this metropolis are “forced to buy” goods, with the promise “of happiness and good health and order,” from “loud advertisements calling to [them] to own things.”