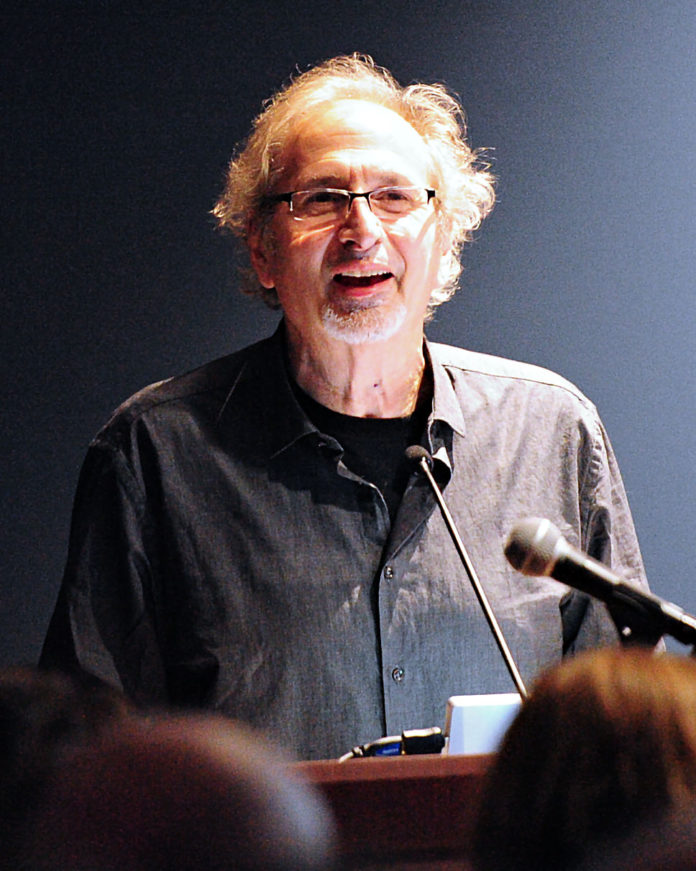

BELMONT, Mass. — Prof. Peter Balakian and Aram Arkun, in their latest collaboration, the translation of a manuscript by Bishop Krikor Balakian, The Ruins of Ani: A Journey to Armenia’s Medieval Capital and Its Legacy, are using Armenians’ sentimental attachment to the ancient capital to shine a light on why indeed the city deserves to be viewed with awe and reverence.

On Thursday, February 27, the two discussed their new book at the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research to a packed audience.

Incidentally, the book received the 2019 Sona Aronian Book Prize for Excellence in Armenian Studies from NAASR.

Marc Mamigonian, the director of academic affairs at NAASR, in his opening comments said that it is “important to make [Ani’s history] accessible to the outside world,” and that the book was “imbuing it with a currency we will hear tonight.”

Arkun, the executive director of the Tekeyan Cultural Association of US and Canada, and assistant editor of the Armenian Mirror-Spectator, a historian by training, started off the program by giving an overview of the grandeur of Ani and the infighting and pettiness that led to its eventual demise.

Arkun said it was important to encourage scholarship in Armenian topics and delved into the significance of Ani.