For many countries, independence day is a routine date in the calendar, when the anniversary is remembered while many of the liberties and opportunities created by that independence are taken for granted.

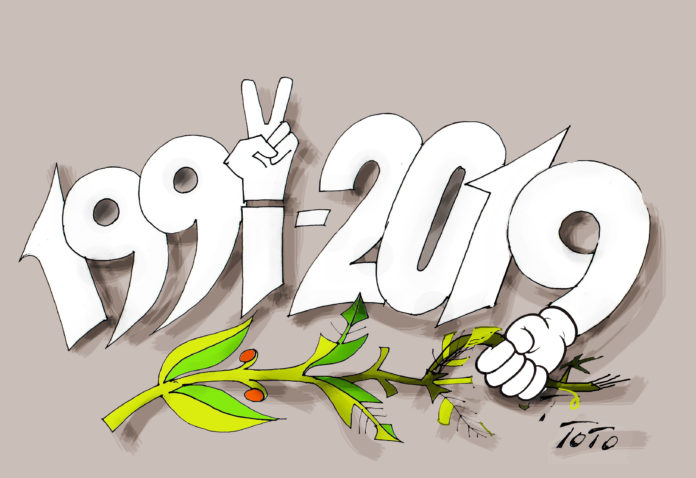

For Armenians, independence has a very special meaning, because we have lost it so many times and rediscovered it through the upheavals of history. It is much more precious, and we have to count our blessings every year that we celebrate independence, because the first independence in the modern era, in the early 20th century, lasted less than three years. When Armenia turned independent again in 1991, the first two and half years presented a threshold, a psychological barrier, which we crossed with the fear of losing independence in our hearts.

The two independence opportunities that were offered to Armenia came to being through international developments; in 1918, independent Armenia rose over the ruins of the collapsed Russian Empire and the second, in 1991, as a result of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Following World War I, a political vacuum was created in the Caucasus, one which the emerging Kemalist movement in Turkey and Lenin’s Bolshevik revolution in Russia were racing to fill. Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan formed a confederation called the Seym, which was meant to hold those three embattled nations together. But the constituent nations had so many historical, territorial contradictions and adversities that the union did not last long and was dissolved as each nation declared independence.

Armenia was the last one to declare almost by default, as Prime Minister Simon Vratzian lamented in his book, that “people were crying like a mother who had given birth to a defective child.”

But even that beleaguered republic emerged to become a country, paying a very steep price as a nation, recently risen from the ashes of the Genocide, had to stand up to the invading forces of Karabekir to create a new Armenia. Were it not for the victory at Sardarabad, Armenia’s current territory would end up as part of the Republic of Turkey.