BOSTON (Boston Globe) — During the 50 years he ran an expansive restaurant empire unlike any other in Boston, Charlie Sarkis strode through life as if it were one of his dozens of dining rooms. His eyes noticed everything: the cut of a steak, the quality of service, the bottom line.

Sarkis, who was 78 when he died Sunday, March 11, in Florida of complications from brain cancer, at one point presided over an abundant list of more than 30 dining destinations that included his flagship Abe & Louie’s, along with Atlantic Fish Company, J.C. Hillary’s Ltd., Charley’s Eating and Drinking Saloon, and the Papa Razzi and Joe’s American Bar & Grill chains.

Complex and unafraid to be combative while fighting to protect the 3,400 jobs at his establishments, Mr. Sarkis was just as well known for owning the Wonderland Greyhound Park in Revere and a harness racing track in Foxborough — gambling pursuits that even admirers found unusual in a man who made no secret of his wish to distance himself from the criminal reputation of his father, one of Boston’s best-known bookies.

Though Sarkis chose very public ways to make his fortune, he was famously private. Yet when he opened up in an interview in 2005, it was to discuss the very personal challenges he had faced recovering from his first brain surgery in 1995 and his efforts to steer others with brain tumors to top-notch doctors. “I’m not as tough as you think, you know,” he told the Globe. “Can I be a pain? All that and more. But I learned we don’t control what we think we control. And you have to pass something on.”

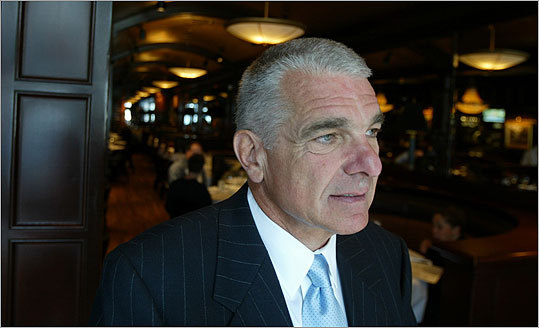

He cut an elegant figure in his dark tailored suits, silk ties, and crisp shirts, but he never ducked a fight to protect his life’s work, whether in a courtroom, a regulatory hearing, or the pages of newspapers where his quotes could slice as sharply as a carving knife.