By Aram Arkun

Mirror-Spectator Staff

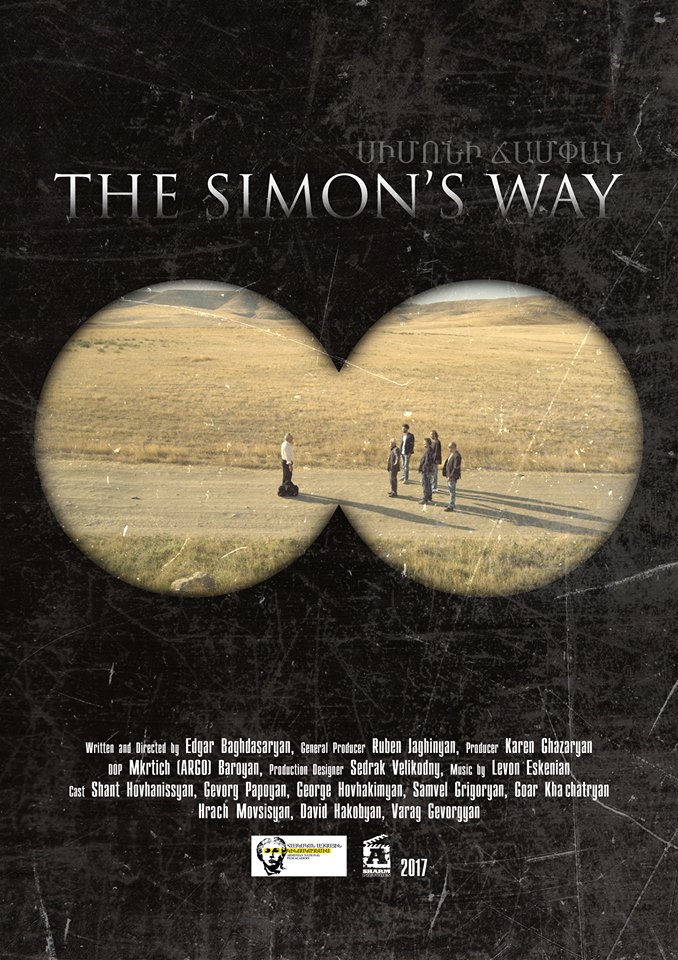

BELMONT, Mass. — “Simon’s Way,” a short feature film from Armenia, will be screened at the Global Cinema Film Festival of Boston in Belmont on Sunday, March 12 at 5:15 p.m.

The Armenian National Film Academy named it the best short film of 2016, while the Direct Monthly Online Film Festival and the Monthly Film Festival both independently recognized it as the Film of the Month for January 2017. A representative of the film production will be present from Armenia to speak and answer questions from the audience after the screening. The presentation is cosponsored by the Armenian Museum of America, and its director, Berj Chekijian, will serve as the moderator of the discussion.

The story of the film itself is a simple one. Villagers in Armenia live on the border with Turkey and for 25 years have talked to one another through signals and binoculars because of the difficulties of crossing the border. Finally the death of an old relative, grandfather Artin, leads the middle-aged Simon, one of the Armenian villagers, to take the risk and financial burden of traveling in a roundabout long path across the border. He must go to Yerevan, then Istanbul and then all the way back via plane, train, bus and foot to the border village in Turkey.

Artin’s children and grandchildren, themselves scattered throughout various Turkish cities like Ankara, Istanbul and Diyarbakir, return for the funeral. Simon, hearing names like Hasan and Mustafa, wonders whether they are Armenian, but they reassure him. They speak Turkish but their passports still are marked “Christian.” Artin Dede leaves Simon the present of the family tree. The death briefly unites the divided relatives.

The film’s director, Edgar Baghdasaryan, explained that the film is fictional, but draws on various aspects of real life. For example, such family divisions exist on the Armenian-Georgian border, and those Armenians with Abkhazian stamps on their passports could not go directly back into Georgian territory or would be imprisoned.