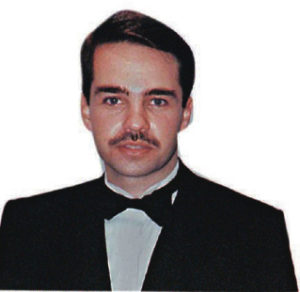

By Robert Jones

In Turkey, a NATO member and a candidate for the European Union, citizens are systematically persecuted or even murdered for having been born non-Turkish or non-Muslim.

For decades, the Turkish government and much of the Turkish public have victimized millions of people -—

Jews, Greeks, Armenians, Assyrians, Kurds and Alevis. Here are six victims whose life stories I hope will give you an idea about what it means to live as a minority member in Turkey.

Like Armenians, hundreds of thousands of Assyrians were also victims of the Ottoman Turks’ genocide of Christians in 1915. They were subjected to “a deliberate and systematic campaign of massacre, torture, abduction, deportation, impoverishment and cultural and ethnic destruction,” Professor Hannibal Travis wrote.