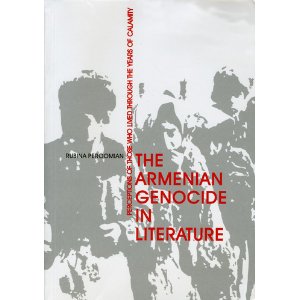

The Armenian Genocide in Literature: Perceptions of Those Who Lived Through the Calamity, by Rubina Peroomian, Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, 2012.

The Armenian Genocide in Literature: Perceptions of Those Who Lived Through the Calamity, by Rubina Peroomian, Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, 2012.

By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

Reading Rubina Peroomian’s new book is not easy, nor is it pleasant. But it is necessary, and highly rewarding. This, her third volume on the subject, deals with the reflections in literature of the Armenian Genocide.

Her first book on the theme was Literary Responses to Catastrophe: A Comparison of the Armenian and the Jewish Experience (1993) and the second was And Those Who Continued Living in Turkey after 1915: The Metamorphosis of the Post-Genocide Armenian Identity as Reflected in Artistic Literature (2008, just republished with a fore- word by Richard Hovannisian).

Her aim is not to prove that the Genocide occurred; that has already been documented by historians. Rather, her powerful work, which she characterizes as “an outcry against man’s inhumanity to man” (p. 14), aims to “expose the human dimension of the crime” (p. xv) and, in so doing, to help second- and third-generation Armenians deal psychologically with the trau- ma passed down to them from their forefathers. She includes herself most directly in this category. At the tender age of 6, she suffered the loss of her father, a chemistry teacher in Tabriz, who was whisked away one night by the Soviet People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) as a leader of the Armenian nationalist opposition. It was that experience which contributed to her decision to learn about the tragedy that had struck the Armenian people. And reading through the voluminous literature was a painful experience, which left its mark on her psyche.

“I want to believe,” she writes, “that the result that I will produce with my work will cure me of my psychological tumult. I pray for a swift recovery, that is the soon-to-come completion of my work” (p. 16).