By Suzanne Muchnic

LOS ANGELES (Los Angeles Times) — If your knowledge of Andreas Gursky’s enormous photographs is limited to meticulously detailed, vividly colored long shots of offices, factories and a 99 Cents Only store, you are in for a surprise.

And if you think Larry Gagosian’s elegant Beverly Hills gallery is a showcase with relatively little floor space, you’d better look again.

The German artist is inaugurating a major enlargement of the gallery with “Oceans,” a new body of work based on satellite images. In his exhibition that opened Thursday night with an invitational preview, six photographs of deep blue water fringed by continents and dotted with islands hang in the new 3,030-square-foot space. Nine earlier works fill the original main gallery and a smaller room upstairs.

“Andreas Gursky is a new relationship for our gallery,” Gagosian says. “He’s one of the most original and innovative living artists, and the timing seemed right with the expansion of our gallery in Beverly Hills.”

For the last 15 years the gallery on Camden Drive has occupied an airy white space with soaring ceilings designed by Richard Meier & Partners. The addition, also designed by Meier’s firm, expands into an adjacent building on the south side. The aluminum-and-glass façade of the new section has the same clean look, but the interior brings a new twist in a curved wood ceiling.

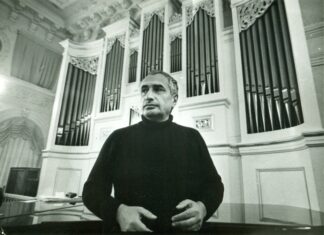

A couple of days before the opening, Gursky is jet-lagged but intensely engaged in the installation of his first show at Gagosian’s international empire of galleries. Slightly built and soft-spoken, the artist is a quiet, thoughtful presence in a scene of precise measuring and heavy lifting, punctuated by high-pitched warnings of a mobile scissor lift.

Plans to put the “Oceans” in the new gallery never changed, Gursky says, but the rest of the show has been a work in progress. His traveling retrospectives haven’t come to Los Angeles, where he has had relatively little exposure, so it seemed like a good idea to back up the new work with older pieces. But which ones? And how should they be presented?

“When we started to do the installation, the ‘Madonna’ piece was here, also ‘Pyongyang,’ “ he says of splashy, high-energy images that have been moved upstairs. He shot the singer at her post-9/11 concert at Staples Center, where she traded the kilt worn on her tour for an American flag skirt. In sharp contrast, “Pyongyang I” depicts a perfectly executed performance of mass calisthenics in a North Korean festival.

“This is a better solution because it’s more conceptually based,” he says of the current arrangement. “The works upstairs show more activity. In this space, the photographs are very empty and melancholy. Someone who doesn’t know my work might think this group is a series. For me, it is interesting to combine images not meant to belong together. When you put them together, it’s about emptiness, it’s about abstraction.”

Born in 1955 in Leipzig, the son and grandson of commercial photographers, Gursky grew up in Düsseldorf and still lives there. He is part of a group of well-known German photographers — including Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth and Candida Höfer — who studied with Bernd and Hilla Becher at Düsseldorf’s Kunstakademie.

“But everything I know about technique, I learned from my father,” he says. “In a way it was an advantage; in another way, a disadvantage.”

A leading figure whose works have brought up to $3.3 million at auction, Gursky became known for merging documentary realism with digital manipulation. Shooting from high vantage points, he often unites multiple pictures in a seamless whole. Gursky goes to enormous lengths to make his pictures. In “Kamiokande,” he gained access to an underground neutrino observatory in Japan that is usually filled with water but had been drained for repairs. In “Beelitz,” he photographed Polish workers in a German asparagus field from a helicopter. The result is a horizontally striped image dotted with tiny people.

“For me, it’s a very metaphorical image. It’s not important that they harvest asparagus. It’s more about human beings in general. These lines could be living things,” he says of the bare earth between rows of asparagus. “Sometimes they are broken or damaged. Sometimes they are straight.”

Gursky maintains a large archive of pictures gleaned from newspapers, magazines, television and the Internet, mining it for ideas that he can develop. But the “Oceans” were inspired by an image of the Indian Ocean he saw on a monitor while flying from Dubai to Australia.

“In this case, I used pictures that already existed, satellite pictures,” he says. But he transformed them, manipulating vast stretches of darkness to suggest various depths of water and leaving the intricately detailed land alone. “If I get some information about the land, why should I change it?”

“The concept,” he says, “was to show the oceans. If you look at a globe, you see that you don’t have so many choices.” He wrapped up the project in six images that more or less map the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. One particularly striking vertical image sweeps through the Pacific from Antarctica to Alaska. In another picture, the tip of Africa hangs between the Atlantic and Indian oceans.

“It’s about our planet,” he says of the new series. “It’s also about the universe because we are not looking at the planet from the planet but from somewhere else. In a way, you can feel that.”