Writing, Reading as Optimistic, Democratic Acts of Faith

By Daphne Abeel

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

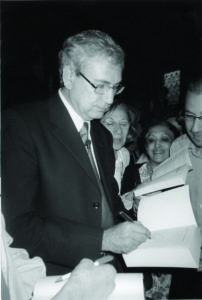

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — On Tuesday, September 22, if Armenian members of the audience at Sanders Theater expected Turkish author Orhan Pamuk to mention the Armenian Genocide in his first Charles Eliot Norton lecture, they were disappointed. What they did hear was a subtle and stunning exposition of the Nobel Prize-winning novelist’s thoughts on writing and reading the novel.

There was a bow to Pamuk’s political sympathies in the introduction by Homi Bhaba, director of the Humanities Center at Harvard, when he characterized Pamuk as a “a defender of pluralism and opposed to dogmatism.” He also described Pamuk as “attentive to the wounds of others.”

But the Norton lectures, Harvard University’s most prestigious humanities series, are not intended to deal with the mundane. Founded in 1925, the Charles Eliot Norton Professorship in Poetry is dedicated to “the term Poetry [which] shall be interpreted in the broadest sense, including together with Verse, all poetic expression in Language, Music, or the Fine Arts.”