By Haykaram Nahapetyan

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

The recent initiative of Armenia’s Parliament’s deputy-chair Alen Manukyan aiming to change Mer Hayrenik (Our Motherland), the national anthem of Armenia, brought back the long-standing historical debate about the origins of Armenia’s number-one national song. Although the history of the lyrics is known, the music remains a matter of discussion. This is an attempt to analyze the known facts on the origins of Mer Hayrenik with some additional research.

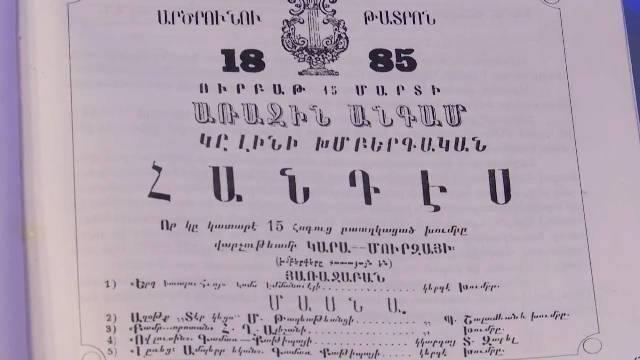

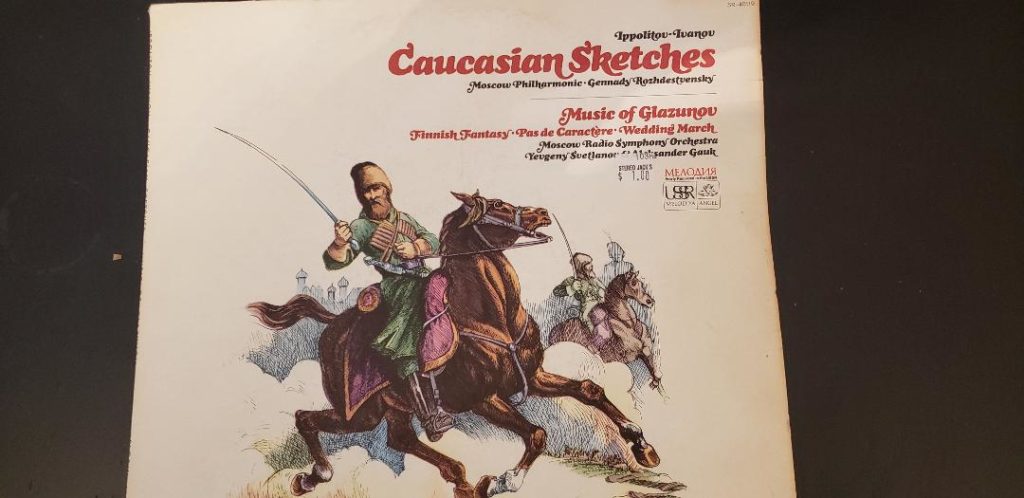

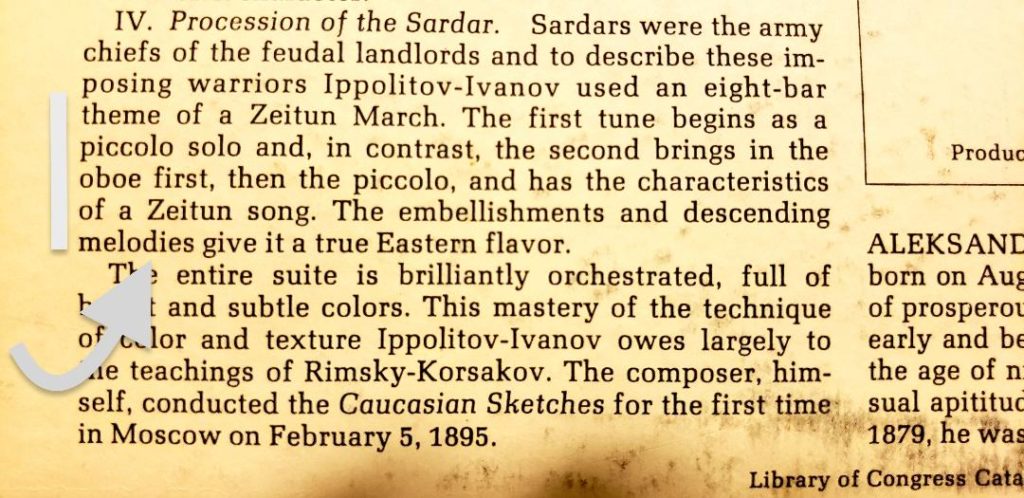

It is on record that Mer Hayrenik was played in Zeytoun (1895), in Van (1915), and during other famous self-defense battles when local Armenian music bands sang it in order to encourage the defenders resisting the Ottoman army’s attacks. According to the Armenian Revolutionary Federation politician Arsho Shahkhatuni, Mer Hayrenik was played in Yerevan while the historic battle in Sardarapat was going on in May of 1918.

Thus, when shortly after the victorious battle Armenia became independent, Mer Hayrenik naturally was transformed into the state anthem of the republic. Simon Vratsian, the last prime minister of the independent Armenian republic, conveys in his memoirs the story of how the flag and the coat of arms have been adopted but makes no mentioning of the anthem. To the best of my knowledge, no memoirs relevant to those historic days detail the story of the adoption of the state anthem. It appears to have happened naturally: Mer Hayrenik was already widely perceived as an anthem even before independence, due to its significant historical background.

The emergence of Mer Hayrenik