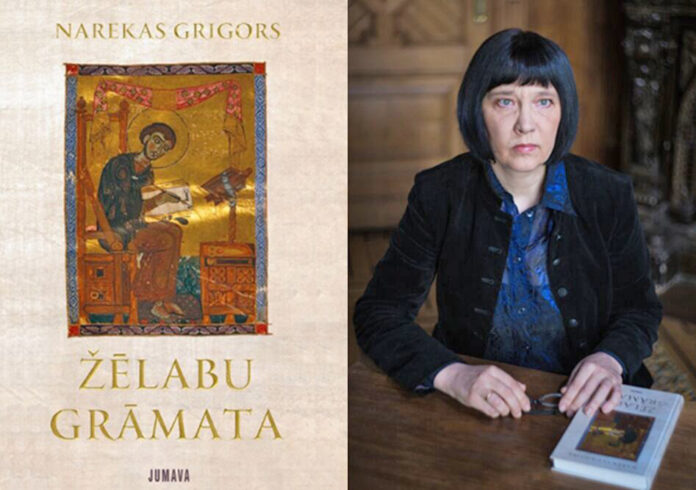

YEREVAN-RIGA — Latvian translator Valda Salmiņa (born in 1962) earned a bachelor’s degree in philology with a specialization in German Philology from the University of Latvia and studied Armenian Philology at Yerevan State University. She also studied at Hagen University in Germany, obtaining a master’s degree. Currently, she works as a German language teacher at the Riga School of Design and Art. She translates Armenian literature in Latvian. In 2018, she was nominated for the 2017 Latvian Literature Annual Award in the category of Best Foreign Literature Translation into Latvian for her translation of Grigor Narekatsi’s The Book of Lamentations from Classical Armenian. For her contribution to promoting Armenian cultural heritage in the Baltic States through the translation of The Book of Lamentations, Salmiņa was awarded the Grigor Narekatsi Memorial Medal by Armenia.

Needless to say, Valda answered my written questions in Armenian…

Dear Valda, in the Baltic republics, Armenology appears to be the most developed in Latvia. How would you characterize Latvian Armenology in the past and today?

We cannot really speak of systematic Armenology research in Latvia. Over the past 20 years, we have carried out several successful initiatives in collaboration with the Latvian Language Institute and the University of Latvia. I have developed proposals for the correct pronunciation of Armenian proper names in Latvian. After completing my doctoral studies, I participated in several conferences both in Latvia and abroad, presenting topics such as the translation of Grigor Narekatsi and onomastics, including Armenian ergonyms in Latvia’s urban environment. In recent years, in cooperation with the Embassy of Armenia, particularly the former Ambassador to the Baltic States Tigran Mkrtchyan, international Narekatsi Readings have been organized at the University of Latvia in Riga.

In November of 2023, a conference dedicated to Nerses Shnorhali, organized at the initiative of Bishop Vardan Navasardyan, brought together luminaries such as Levon Boghos Zekiyan, Claude Mutafian, and Abraham Terian. Reports were delivered by art scholar and Vice President of the Latvian Academy of Sciences, Ojārs Spārītis, church history professor Andris Priede, and religion scholar Prof. Elizabethe Taivane, who has Armenian roots. She has been traveling around Armenia for several years, collecting materials on the manifestations of the people’s religiosity. Prof. Taivane has managed to unite scholars working on a collection of articles titled Armenia through the Eyes of Latvians, which will be published by the University of Latvia Press.

Today, we have two Armenian translators who translate Latvian writers from the original. How is Armenian literature presented in Latvian?