By Harry Mazadoorian

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

Worshipping in the sanctuary of the Armenian Church of the Holy Resurrection in New Britain, Conn., always evokes feelings of comfort and security for me. I am encapsulated in warmth, reflection and safety.

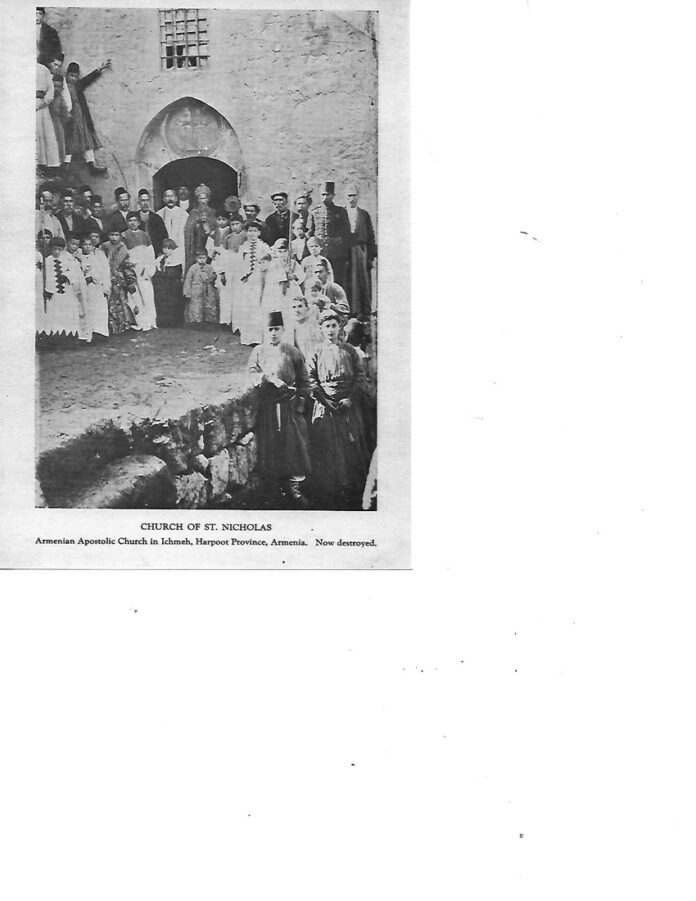

My thoughts, however, sometimes turn to a time almost 110 years ago, in a little remembered village named Ichme in the former Ottoman province of Kharpert. There, I imagine my grandfather, Garabed, also being in the local Armenian Church, that one named St. Nicholas or Soorp Nigoghos.

But I imagine for him not the sanctuary of peace and security that I enjoy: rather I think of just the opposite.

I think of a horrible time when the sanctity and safety of the church was shattered, on the eve of the Armenian Genocide of 1915 when more than one and one half million ethnic Armenians ultimately perished at the hands of the Ottoman Empire.