Even though increasingly doubtful and scared, the internationally acclaimed photojournalist Anush Babajanyan from Yerevan, Armenia, kept returning to that “special place” whenever she could, “partly because Armenians, like me, lived there,” but also because “the story of this place and its people had not been told enough, and I wanted to tell it.”

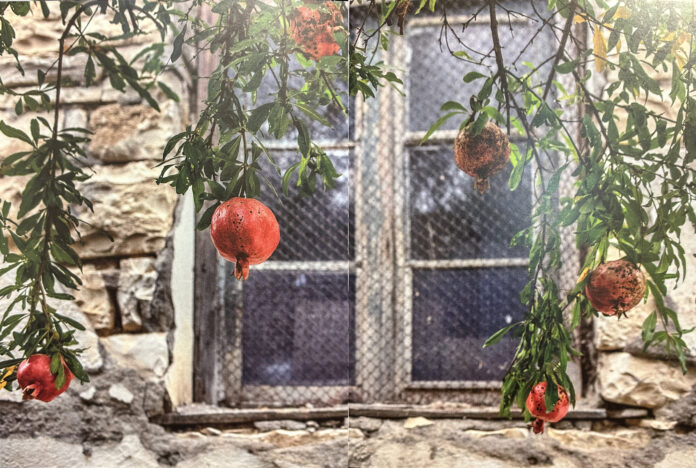

What started off as a documentation of the natural beauty and the ordinary life of the families living in the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh) ended up being a documentation of loss. “Nature in that unknown yet familiar place felt more gorgeous even when we didn’t know we were going to lose it,” says the artist with much emotion. The ninety-nine photographs comprising Babajanyan’s recently published A Troubled Home (EBS, 2022) tell the stories of the families who, following the dissolution of the republic in 2023, were forced out of the land they had called home for millennia to become refugees trying to resettle to a new life.

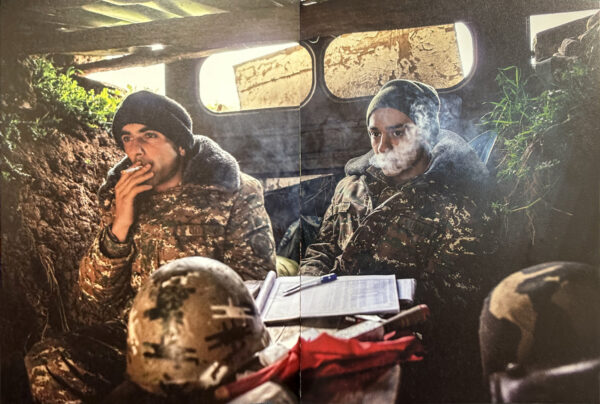

Babajanyan made her first trip to Artsakh on April 2, 2016. Notwithstanding the ongoing fighting between Artsakh and neighboring Azerbaijan, she kept going back and forth, actively photographing even in regions ceded to Azerbaijan following 2020’s 44-Day War. It was in 2020 that she decided to bring together the work she had done for five years.

The photographs assembled in the elegant volume owe their tremendous appeal to the intimate relationship Babajanyan had with the families. “I had unimpeded access into their homes. I was not an intruder. I am still in touch with them,” she notes candidly. Her pictures are of real people with real names. Only a photographer sharing her subjects’ most familiar space could capture the everyday joys and sorrows the shots convey to the viewer. When asked about the amazing power her work has to touch people, “Once the personal connection is established, photography follows,” she adds.

It was especially the lives of the many large families in Artsakh that Babajanyan wanted to document, as the photo of Liana Babayan happily introducing her newborn son, Movses, the Babayans’ tenth child, to her children at the Stepanakert maternity hospital attests. A mother herself, it was Babajanyan’s genuine concern for the families that won their confidence. There are pictures of children playing joyfully inside their homes, and outside in their backyards while the mother hangs the laundry to dry. Photographs of the entire family seated at the dinner table strewn with numerous dishes abound. Why so many children? How does one feed a family of 12?

Whether it is of the young woman at the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral in Shushi lighting 31 candles and putting them together in a tight bunch, one for each year of the age of her friend who was missing in action, of the seven children lined up against the wall of their old apartment waiting for their new home, or of the endless flow of cars during the week-long exodus from Artsakh, the photos reveal the woman who cares deeply for her fellow human beings and for her native land.