Shushanik Kurghinian, the almost forgotten, revolutionary prose and poetry writer from Alexandrapol (present-day Gyumri, Armenia), according to noted literary critic Marc Nishanian, “one of the greatest writers from the eastern part of the Armenian world,” and Zabel Yesayan, the prolific writer from Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey), accused during Stalin’s Great Purge of national activism, imprisoned,and eventually “disappeared,” are two early 20th-century voices that have been largely silenced, at least until recently.

Taking upon herself the task of rectifying this historical injustice, Shushan Avagyan, a radical young writer currently living in the Republic of Armenia, imagines an encounter between the two women whose lives briefly overlapped in the city of Yerevan in the year 1926.

This fictional encounter takes (or doesn’t take) place in Girq-anvernagir (Yerevan, 2006), an experimental novel Avagyan wrote while working on translating a selection of Kurghinian’s poems into English. The novel opens “One day in spring” with a meeting in a cafe on Abovyan Street in Yerevan between the narrator, referred to throughout as “the typist/writer” (Avagyan?) and Lara Aharonian, who in 2008, along with Talin Suciyan, directed and produced the documentary “Finding Zabel Yesayan,” just as the historical protagonists might have done “if they’d met each other in 1926, one day in spring.” Shushan and Lara had met in the early 2000s and decided to research the lives of Yesayan and Kurghinian together to rediscover the story that “was deliberately made to disappear.”

Avagyan was well-aware of the “careful, intentional, and organized disavowal” of Kurghinian, to borrow Nishanian’s words once again. Indeed, both Yesayan and Kurghinian had been black-listed because they spoke for justice and dared step outside the role prescribed to them, both as women and as citizens of oppressive regimes, the Ottoman Empire and Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union respectively. Kurghinian recalls being reproached and belittled “for holding a pen,” even as she insists, “break my fingers one-by-one . . ./ they weren’t created for embroidering.” Ironically, when in prison, Yesayan asks her daughter Sophie for embroidery thread. “In 1939 she’d often send us postcards embroidered with red thread,” writes Sophie.

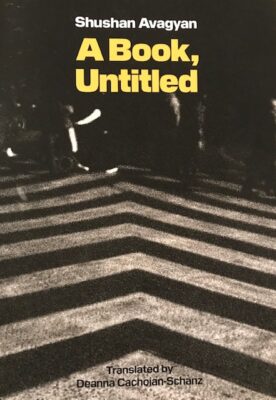

As the novel unfolds, the voices of the typist/writer and of Lara and the historical protagonists intermingle. Lines from Kurghinian’s poems, interspersed throughout the book with no quotation marks, often make it difficult to know whether the words are Avagyan’s or the poet’s. What starts off as a story authored by Avagyan ends up being the stories of four women whose lives overlap, “one spring day” in Yerevan. In fact, A Book, Untitled (Awst Press, 2023), Deanna Cachoian-Schanz’s translation of Girq-anvernakir, from the original Eastern Armenian into English, comes to add a fifth “contributor.” While Cachoian-Schanz strives to preserve Avagyan’s “unique voice,” she also reckons that the translation is always a “recreation” of the original, in her words, “a renewed reading of the primary text.” “Dear reader, you are not reading Girq-anvernagir. You are reading A Book, Untitled. If you want to read Girq learn Armenian!” she writes. Her “Note on Book and Its Historical Protagonists” and “Translator’s Afterword: Deviations” further illuminate the reader and make Cachoian-Schanz, in her own words, “an equal player” in the creation of the “original” text.

Interestingly, rather than disorient and alienate, these deviations from more conventional narrative practices — Avagyan’s mixing of multiple voices, her fragmented prose and ongoing reflections on her “experiment,” and Cachoian’s own “deviations” — keep the reader engaged. Opening up the text to new possibilities makes this postmodern experiment an ally to a more equitable future. The authors’ commitment to reversing the injustice by bringing silenced voices back into history, in their words, by “re-remembering the erasure,” is extremely appealing. A Book, Untitled is a book one does not want to put down.