POTSDAM, Germany — Scholars and human rights proponents who came together earlier this month for a conference on “Genocide and Denial,” were continuing a discussion process begun in January this year. As Lepsiushaus director Dr. Roy Knocke recalled, the first conference, addressed by Prof. Taner Akçam and German Holocaust historian Wolfgang Benz, dealt with the denial of the Shoah and the Armenian Genocide as viewed from the historical perspective, whereas the second session would “develop the theme further, from a philosophical, sociopsychological and juridical perspective, with reference to human rights practice.” As referenced last week, all these aspects were treated in depth by experts. (See story in last week’s issue.) To do justice to all the presentations would require far more than an article, and what follows is a summary report. It is hoped that the papers will be published in the near future.

The Discrete Individual

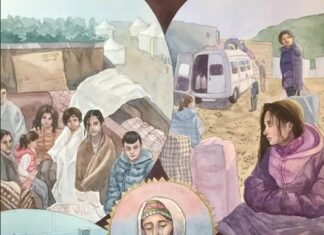

If understanding the juridical aspects of genocide denial is crucial to effective action by human rights proponents in the pursuit of justice, grasping the nature of the social and psychological dimension of the phenomenon is vital to appreciating the human experience. Genocide involves entire populations and cultures, but it is perpetrated by individuals and they destroy the existences of individuals. How can one explain the mind of a perpetrator who denies his criminal actions? And, how may one access the emotional impact on the survivors and their progeny?

Dr. Angela Moré, professor of social psychology at Leibniz University, Hannover, offered profound insights into these questions in her talk on “Denial of Crimes against Humanity: Motives, Mechanisms and Consequences.” Among the defense mechanisms defined by psychoanalysis, denial serves to protect the ego from feelings of shame, fear and guilt, and it does this by creating constructs; in the attempt to deny a past deed, one creates an alternative version of events, as in an alibi or an outright lie. (Interestingly, in German the words for denial and lie, Leugnen and Lügen, are etymologically linked, sharing the same root.) For example, a German World War II veteran, who had told his family he had been a prisoner of war in Siberia until 1949, actually had been released from an English prison in 1945, where he was serving time for car smuggling. The lie about Siberia served to protect him from the shame associated with his own criminal act, while also eliciting recognition and sympathy.

Or, denial may function as a form of dissociation; here one eliminates any empathy for the victim, by depriving him of his humanity. Moré cited the example of a Nazi SS member who proudly boasted of his executions of Jews with the construct that, if not eliminated, those victims could have done the same to his offspring. A group dynamic denoted as a “Soldier-Matrix” refers to perpetrators who experience their own brutal actions with feelings of superiority and power. Having denied the humanity of their victims, they end up destroying their own humanity.

Some perpetrators, Moré reported, might attempt to repair for their crimes, once returned to civilian life, but others would not. On the contrary, as amply documented in accounts of war crimes trials against Nazi perpetrators, they would flatly deny any wrongdoing, and, bound together in a sort of “sworn community,” rely on one other to hold up the lie. Furthermore, as an expansion of this phenomenon socially, significant layers of the civilian population would claim they had had no inkling of what had been laid bare in the war crimes tribunals.