YEREVAN/GIZA, EGYPT — Ahmed Magdy Hammam (born 1983) is an Egyptian novelist, storyteller and journalist. Ahmed started working as a cultural journalist since 2010, collaborating with Al-Ahram, Akhbar el-Yom, Al-Dustour, and other media. He was also the editor-in-chief of the World of Books magazine. He has published many fictional and short stories in the Egyptian and the Arab periodicals, publications, and websites. Hammam participated in many cultural and artistic conferences and events in Egypt and abroad. His books have been published in Cairo, Dubai, Dammam and Beirut, including: From Cairo (novel, 2008), Ibn Awaa’s Pain (novel, 2011), The Gentleman Prefers Losing Cases (short-story collection, 2014), The Story Factory (25 interviews, 2016), Ayyash (novel, 2017), Recipe No. 7 (novel, 2017 and 2018), Reports to Sarah (diaries) (2019), etc. His works have valued him awards (including the Sawiris Cultural Award), as well as recognition of criticism and a wide circle of Arabic language readers.

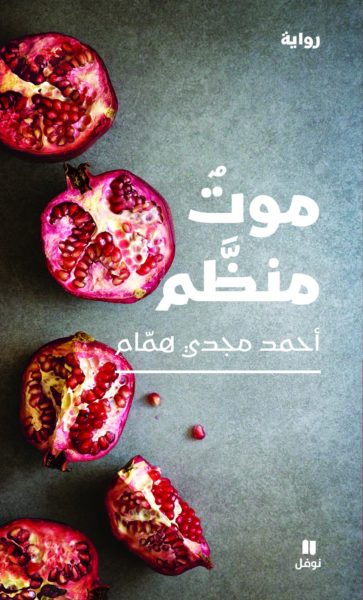

We Armenians learned about Ahmed Majdi Hammam when his novel Organized Death on the Armenian Genocide was published this year. “With his latest novel Maout mounazzam (Organized death), writer Ahmed Majdi Hammam, a serious and melancholic voice that comes from deep Egypt, uses a certain shocking title but that says a lot about his narrative. A story announcing the setbacks, expectations and tragedy of humans in front of an unfair, torturer, greedy, and bloody and unpredictable society” (Edgar Davidian, L’Orient-Le Jour).

Ahmed, first of all it will be interesting to know about your personal and educational background, as well as where you work now.

I was born in the UAE to Egyptian parents, and I grew up there in the city of Al Ain, in Harat al-Souriin (Syrian Quarter) neighborhood in a Bedouin environment. This blending of Gulf, Syrian Levantine and my own Egyptian culture contributed greatly to giving me a unique cultural mix.

When I returned with my family to Egypt, I studied Arabic language and literature at the Faculty of Education at Helwan University. Currently, I work as a cultural editor for Al-Dustour daily. I also write for some Arab newspapers and websites as a correspondent from Cairo.