By Anaïs DerSimonian

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

BOSTON — A lot has happened in Armenia over the last couple weeks – Azerbaijan has waged a regional war during the COVID-19 pandemic, firing on border villages, bombing a PPE mask factory and threatening to bomb the Armenian Nuclear Power Plant. Events like this are hard to process for Armenians around the world; how could this happen? Where do we go from here? What’s next?

For young diasporan Armenians living in the United States, the mental and emotional weight of this recent conflict is only exacerbated by current public health and social tensions nationwide. Despite recent “re-openings” across the country, the U.S. has exponentially more COVID-19 cases and deaths than any other nation and concurrently, the Black Lives Matter movement continues to demand change at a systemic level.

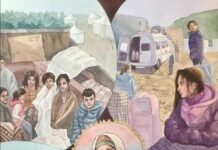

From Lilit Danielyan’s “Villagers” series

Armenia’s diaspora has an expansive history of coping with trauma and tragedy through art. Take Genocide survivor and visual artist Berj Kailian for example – she was exposed to the atrocities of war as a small child, and spent the rest of her life creating breathtaking works of art that not only provided her with a coping mechanism, but also her art became an abstract portal into Armenian history for the younger generations.

With the social and political upheaval both in Armenia and the States, let us take a look at what three young female Armenian artists – who are distinct in their identities as well as their crafts – are doing to explore their identity and to cope with the times.