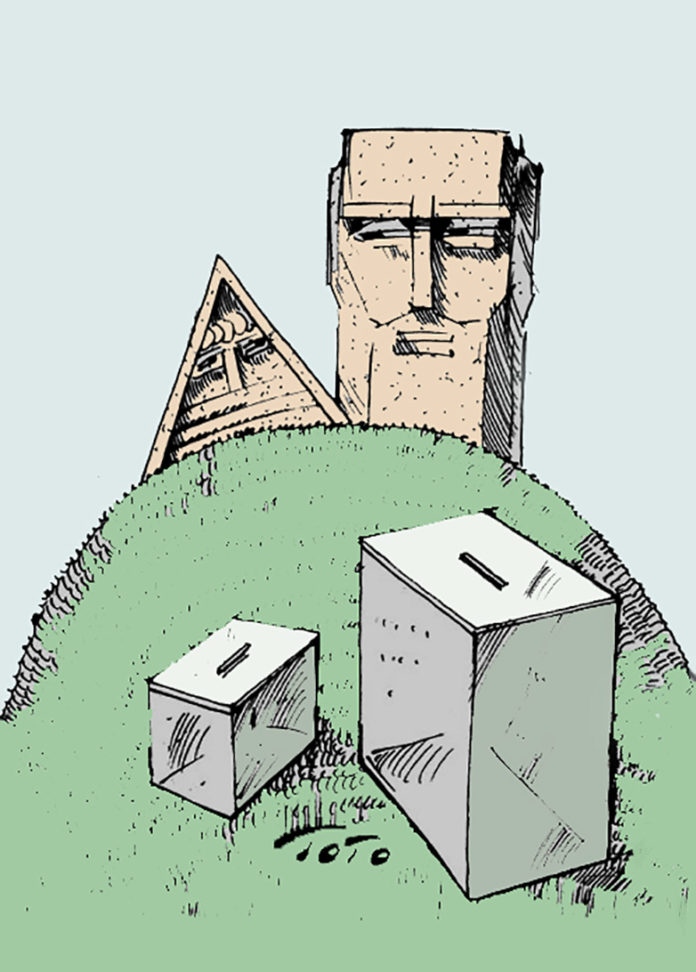

Karabakh, or the Republic of Artsakh, its more recent official title, has developed into a self-contained, independent political entity, with all the attributes of a full-fledged state. It has held orderly and frequent transparent elections to maintain its governance. In addition, although global political structures have not endowed the republic with official recognition yet and continue to issue statements about their refusal to acknowledge the election results, they understand deep down that Karabakh is not a breakaway rebel territory under the rule of warlords.

And thus, the people and the state of Karabakh take themselves seriously and continue to rule the republic under a constitution based on democratic principles.

The Armenian people in Armenia and Karabakh organize local and national elections meticulously, inviting international observers to monitor the election processes and issue their opinions.

On March 31, 2020, legislative and executive branch elections are set to be held in Karabakh. At this time, 27 political parties have put forth their candidates for 33 seats in the parliament. There are 14 presidential candidates in the running. The campaign was officially launched on February 26.

Karabakh maintains the presidential system, unlike Armenia which switched to a parliamentary one.

Karabakh is a contested territory between Armenia and Azerbaijan and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group has been holding negotiations since the May 14, 1994 ceasefire took hold to try to settle the conflict.