For international observers, the Karabakh conflict is viewed within the perspective of the Kashmir and Korean issues, where militarized camps are always on the brink of war.

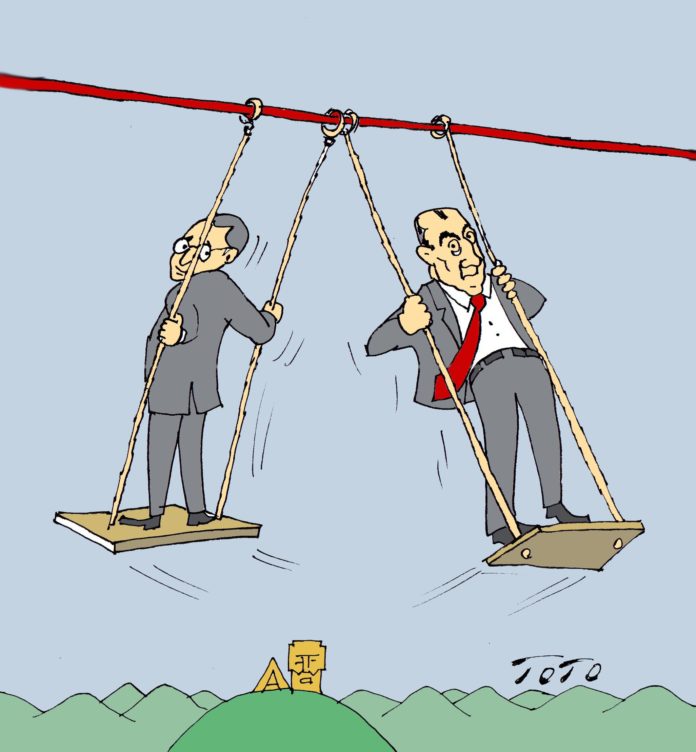

After meeting five times in 2019, the foreign ministers of Armenia and Azerbaijan met again in Geneva January 28-30 for a total of 12 hours. The intensive pace of negotiations and the fact that the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk group co-chairs, who have sponsored those negotiations, have issued the code words “preparing the two nations for peace,” indicate some kind of compromise is in the offing.

However, the details of the negotiations are being kept under wraps, leaving pundits and analysts in complete limbo to reach their own interpretations of the developments.

Some domestic and international issues always impact on the course of the talks. The fact that the peoples of Karabakh and Azerbaijan are in the process of preparing for elections rule out the potential for imminent escalation.

Another factor is a departure from the rhetoric of the previous administration in Armenia, which always avoided a war of words, or, at the very least, kept it to a minimum.

This time around, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan himself has announced that Armenia has recently acquired large quantities of sophisticated military hardware. The military brass in its turn has announced that it was in the process of revising its military doctrine to wage war on the enemy’s territory.