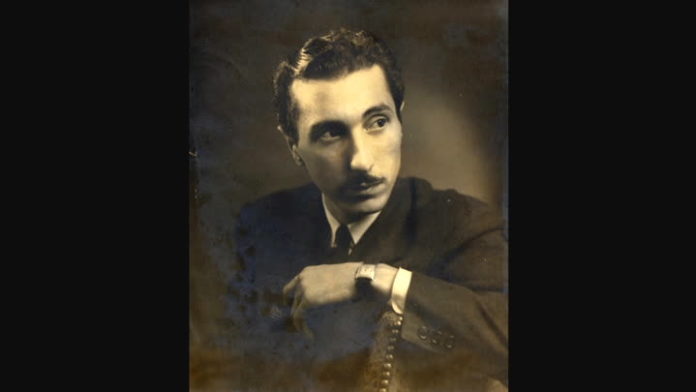

MILWAUKEE, Wis. (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel) — A 104-year-old Milwaukee photographer who survived the Armenian genocide, shot photos of President Franklin Roosevelt and saw Babe Ruth play at Yankee Stadium has died.

Artin Haig died Monday, March 4, of natural causes at St. John’s on the Lake where he lived.

In an interview with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in December, Haig talked about the incredible things he did and witnessed in his eventful life. That included watching his favorite players Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth while he lived in New York.

“I used to go to baseball games and I used to sit on the third base side because I liked to see them steal home,” Haig said.

Haig would have turned 105 in August.

In an earlier interview with the paper, he had said, “I used to go to baseball games and I used to sit on the third base side because I liked to see them steal home.”