By Bilgin Ayata

A century after the Armenian Genocide and its ongoing denial by the Turkish state, there has emerged a notable and unprecedented interest in the Armenian past and present both in civil society discourse and scholarship in Turkey, accompanied by various reconciliation initiatives at the state and society levels. Observers have suggested that this increased engagement with Turkey’s suppressed past is an outcome of its European Union (EU) candidacy, the democratization reforms of the early 2000s, and the shockwave among liberal segments of Turkish society caused by the 2007 assassination of Armenian journalist Hrant Dink. I argue that this shortsighted analysis, which completely ignores the Kurdish movement’s transformative challenge to Turkish denialism since the 1980s, echoes the key fallacy of present discussions of Turkey’s engagement with its past: compartmentalization and disjunction of interlinked state crimes.

One of the most curious features of the reconciliation debates in contemporary Turkey is the coexistence of various reconciliation processes that occur in complete isolation from each other. Similar to the Armenian Genocide, other topics suppressed by official state narratives, such as violence against Kurds and Alevis, have been increasingly challenged and debated, yet no links have been drawn between them. This is particularly surprising given that some state practices associated with the genocide, such as displacement and dispossession, not only continued during the republican period but constitute key elements of nation making—along with forced assimilation—in Turkey. After the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923, these practices were applied to Kurds and Alevis, while pogroms against and deportations of the remaining Armenian and Greek population continued periodically into the late 1950s. Until 1991, the very existence of a Kurdish identity was officially denied and the use of the Kurdish language was banned. Given that the Kurds constituted roughly 20 percent of Turkey’s population, the entire state apparatus, from the military to the education system, had to be put into service to suppress Kurdish culture and identity.

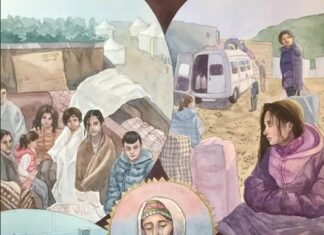

With the formation of the Partiya Karkeren Kurdistan (Kurdistan Workers’ Party; PKK) in 1978 and its armed struggle against this suppression, the Kurdish conflict—as it is referred to today—has since dominated the political agenda of Turkey, shaking up profoundly the country’s politics of denial. The Kurdish struggle forced the state to revise its policy when in 1991 President Suleyman Demirel officially admitted that the Kurds exist—a milestone in the history of modern Turkey. Although the suppression of the Kurds only intensified after this admission, with state security forces displacing 1 to 3 million Kurds from their homes and carrying out other grave human rights violations, the genie was already out of the bottle: state ideology based on the myth of a homogeneous Turkish nation-state had been irreversibly cracked, enabling further questioning of national myths and practices.

While the Kurdish movement’s successful challenge to official denial is certainly not the single explanation for the increased interest in questioning official history, it is rather puzzling that the Kurdish and Armenian issues are treated in disjunction from each other in the current pluralist re-negotiations of national identity and history by liberal segments of civil society. I argue that this is due to a tendency of scholars and civil society to treat the Armenian Genocide as a problem of the past, and the Kurdish conflict as a problem of the present. Such a compartmentalization obscures the complex but important question of ruptures and continuities in Turkish state discourse and practice.

While the chronology, extent, and practices of state violence against Armenians, Kurds, Alevis, and other persecuted groups vary, these groups share subjection to the politics of denial in the Turkish Republic. Whereas the official denial of the Armenian Genocide and of Kurdish identity is known at the international level, the denial of mass violence against the Alevis, such as the Dersim Genocide in 1938, has only recently received domestic attention in Turkey.