By Edmond Y. Azadian

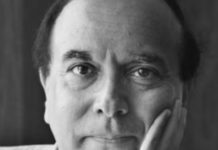

Hrant Dink proved to be a figure larger than life. His frame, while slender, cast a giant shadow. He inspired confidence and radiated power and determination. He used to suck the air out of the room as he entered a place. But his legacy came to match and surpass his attributes while he was living.

He was gunned down five years ago on January 19, 2007. He was silenced at that moment but his message resonates even louder today throughout Turkey and beyond. His assassination was a spectacular event, but what followed was even more spectacular, although unexpected; thousands of people demonstrated in Istanbul in protest, chanting “We are Hrant Dink,” “We are Armenian.”

He was an iconoclast of sorts. When he began publishing his weekly, Agos, in 1996, he had to break certain traditions. He had to overcome certain established modus operandi in the community and then even more so throughout the rest of Turkey.

The Armenian press was at a critical point in Turkey when he founded Agos. The major dailies, Marmara and Jamanak, were losing readership, not necessarily because of a decline in quality but mainly through the retreat of the Armenian language. To switch from Armenian to Turkish, or to any other language, was considered a betrayal, but in the meantime, because of the language barrier, the Armenian youth was deprived of the message. Someone had to take bold action to reach out to the youth. The media in the US had encountered that dilemma in the 1930s when English-language publications appeared to keep the community informed and cohesive, through a lingua franca.

It was Hrant Dink who took that bold initiative and began publishing Agos in Turkish, reserving some pages for the Armenian section.