By Alfred de Zayas

Murder has been a sin since Cain killed Abel, long before the first attempts by lawyers to codify penal law, before the Hammurabi and other ancient codes. More fundamentally, murder is a crime by virtue of natural law, which is prior to and superior to positivistic law. Crimes against humanity and civilization were crimes before the British, French and Russian note condemned the Armenian massacres in 1915. Genocide was a crime before Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944.

According to article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, general principles of law are a principal source of law. Not only positivistic law — not only treaties, protocols and charters — but also the immanent principles of law are sources of law before the ICJ and can be invoked. Among such principles are “ex injuria non oritur jus” which lays down the rule that out of a violation of law no new law can emerge and no rights can be derived. This is a basic principle of justice — and of common sense. Another general principle of law is “ubi jus, ibi remedium”, where there is law, there is also a remedy, in other words, where there has been a violation of law, there must be restitution to the victims. This principle was reaffirmed by the Permanent Court of International Justice in its famous judgement in the Chorzow Factory Case in 1928. Another general principle is that the thief cannot keep the fruits of the crime. Another principle stipulates that the law must be applied in good faith, uniformly, not selectively. Thus, there is no international law à la carte.

And yet there are those who claim that the Armenians have no justiciable rights, because the Genocide Convention was only adopted 1948, more than 30 years after the Armenian Genocide, and because treaties are not normally applied retroactively. This, of course, is a fallacy, because the Genocide Convention was drafted and adopted precisely in the light of the Armenian genocide and in the light of the Holocaust. Not only the Armenian Genocide but also the Holocaust predated the Convention, and no one would question the legitimacy of the claims of the survivors and descendants of the victims of the Holocaust, simply because the Nazi atrocities were committed before the entry into force of the Genocide convention. Moreover, this argumentation is a kind of red herring, intended to confuse and to distract attention from the legal basis of the Armenian claims. Indeed, the rights of the Armenians do not derive from the Genocide Convention. Rather: the Genocide Convention strengthens the pre- existing rights of the Armenian to recognition as victims, to restitution and compensation.

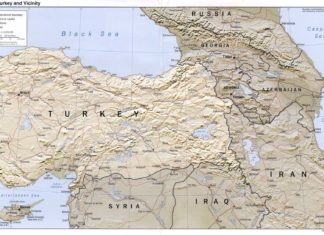

Articles 144 and 230 of the Treaty of Sèvres, signed on August 10, 1920 by four representatives of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed VI, recognized the rights of the survivors of the extermination campaign against the Christian minorities of the Empire, including the Armenians, the Greeks from Pontos, the Chaldeo-Assyrians, and affirmed the obligation of the Turkish State to investigate these crimes and punish the guilty. Article 144 stipulated in part:

“The Turkish Government recognises the injustice of the law of 1915 relating to Abandoned Properties (Emval-i-Metroukeh), and of the supplementary provisions thereof, and declares them to be null and void, in the past as in the future. The Turkish Government solemnly undertakes to facilitate to the greatest possible extent the return to their homes and re-establishment in their businesses of the Turkish subjects of non-Turkish race who have been forcibly driven from their homes by fear of massacre or any other form of pressure since January 1, 1914. It recognises that any immovable or movable property of the said Turkish subjects or of the communities to which they belong, which can be recovered, must be restored to them as soon as possible, in whatever hands it may be found…”