BELMONT, Mass. — The possible — and even highly probable — destruction of all the irreplaceable Armenian moments in Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh), now under Azerbaijani rule, the reasons why monuments matter as well as why they are targeted for destruction, are covered in a new book, Monuments and Identities in the Caucasus: Karabagh, Nakhichevan and Azerbaijan in Contemporary Geopolitical Conflict (Brill, 2023).

The book’s two co-editors and a contributor, Dr. Igor Dorfmann-Lazarev, who teaches at Sofia University, in Bulgaria; Haroutioun Khatchadourian, an independent researcher in France and Dr. Marcello Flores, formerly of Università di Siena in Italy, participated in an online discussion hosted by the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research on April 26. Dr. Sebouh D. Aslanian of the University of California, Los Angeles, offered introductory remarks at the discussion.

The book is the first multidisciplinary volume about Armenian monuments in historic Armenian lands, now under Azerbaijani rule. Much of the work, as well as the NASSR discussion, focused on not only the destruction of those monuments, but also the roots of disinformation campaign by the Azerbaijani government regarding the history of those monuments.

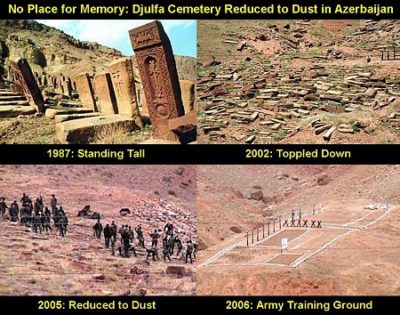

Aslanian started the talk by detailing the century-long efforts by successive Azerbaijani governments of deleting Armenianness from its lands. He ascribed the penchant for a revisionist history in Azerbaijan to Turkey, where dating back to the late Ottoman days, many people in power — seldom historians — wrote history books deleting Armenians from their historic lands.

One such person he cited as an example was Riza Nur, an Ottoman official. “In 1918, an Ottoman Turkish official, Riza Nur, who five years later would become an important representative of the Turkish delegation at Lausanne, wrote a one-volume history,” Aslanian said, “in which he drew from the depths of the collective Pan-Turanist” imagination to present an alternate history. In his book, Aslanian said, Nur wrote that “for 4,000 years or since at least since 2000 BC, the true autochthonous (indigenous) population in central and eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus and the territory of what is the Caucasus are the Turanians.”

Of course, that is not true.