To free us from the expectations of others, to give us back to ourselves—there lies the great, singular power of self-respect.

Joan Didion

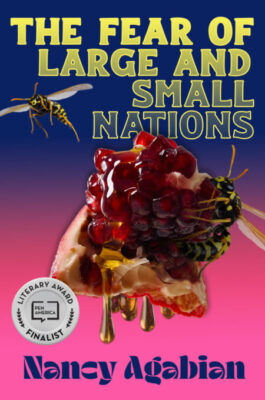

Long one of the most thought-provoking Armenian-American intellectuals, going back to her days as a punk lyricist and her 20-something memoir Princess Freak, Nancy Agabian continues to influence the culture. Her latest work, The Fear of Large and Small Nations, doubles as both a multi-genre novel and a feminist primer on building self-worth and emerging from abuse to boldly take control of one’s life.

This isn’t always easy for Armenian women who must not only shoulder often unreasonable expectations to somehow be perfect mothers and wives, but also fight patriarchy and contend with the weight of recent history. Genocide, war, sovietization — the list seems endless at times. Here, Agabian also writes from the distinct standpoint of a diasporan. This universalizes her project. While the diasporan’s search and longing for roots is a commonplace of sociology, Agabian pulls back the wallpaper on Armenian society to show that they too fear and long for things that they sometimes can and sometimes cannot perceive.

The Fear of Large and Small Nations tells the story of Na, an Armenian-American woman in her late 30s who embarks on the trip of a lifetime to teach English at a well-known university in Armenia. Na has some deep-seated reasons for wanting to fly almost 6,000 miles to this small, landlocked country in the Caucasus, seemingly always at odds with its neighbors or with itself. The daughter of two Armenian Genocide survivors, Na is not only trying to learn more about her heritage. Rather, she is also trying to fill a void that she cannot quite identify. Still single and nearing the end of child-bearing age, Na knows that culturally and otherwise she finds America somehow wanting. This comes through in wry one-liners and observations that Na makes throughout the book, particularly as she is packing in New York City for the journey in September 2006, which includes a veiled criticism of capitalist production and the idea that industrial R & D can make us happy: “I cannot take any fluids or gel-like substances in my carry-on luggage. This new measure must be making the product development people at Dr. Scholl’s miserable. Their state-of-the-art gel shoe inserts are now forbidden… Other items on the list also seem questionable: liquid mascara, for one. I highly doubt that other’s enough room in such a tiny bottle for a harmful amount of explosive material.”

Na does not speak Armenian fluently and does not really feel wholly Armenian either. Inside a deli on her first night in Yerevan, she has a first telling interaction with the Armenian language and culture: “Na was relieved to remember the word for bread, and the word for butter too (…) but she didn’t know how to make a sentence (…) The translation of the Armenian in the imperative mood was, ‘Give me the bread,’ which sounded rude. Saying ‘I want the bread’ sounded primitive. Finally, she pointed to a loaf behind the clerk’s head and said ‘Hahts?’ very softly, her voice like that of a young woman. The clerk stared at Na, a fully grown woman. Na was so embarrassed by her inability to speak Armenian that she lowered her eyes and wordlessly slipped out the open door.”