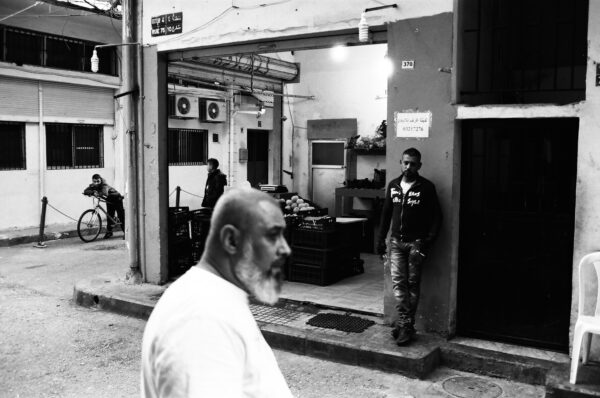

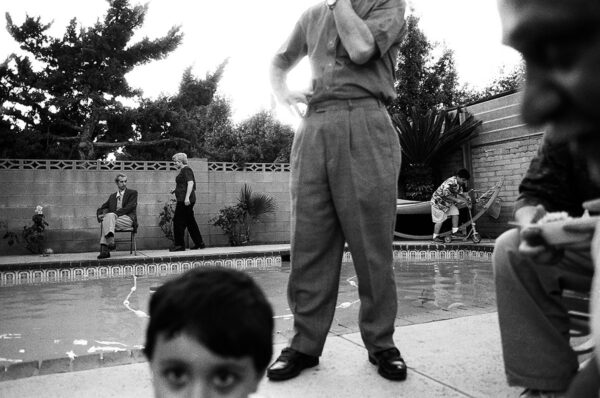

WATERTOWN— A new exhibit of photographs at the Armenian Museum of America tries to weave together the different strands of Armenian communities around the world. The exhibit, “Ara Oshagan: Disrupted, Borders,” opened on June 7 and will continue through October 29.

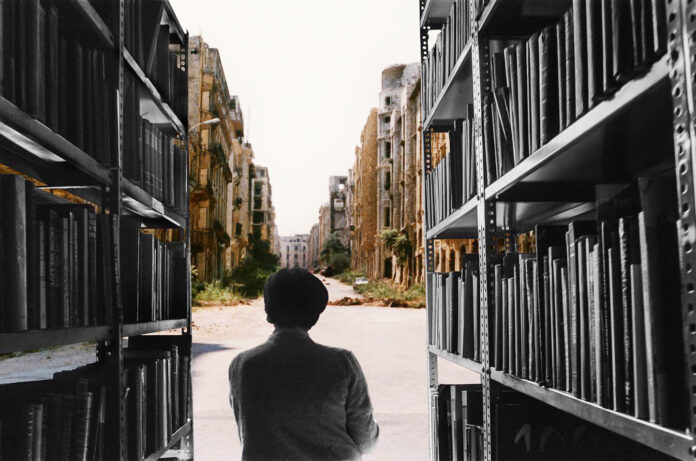

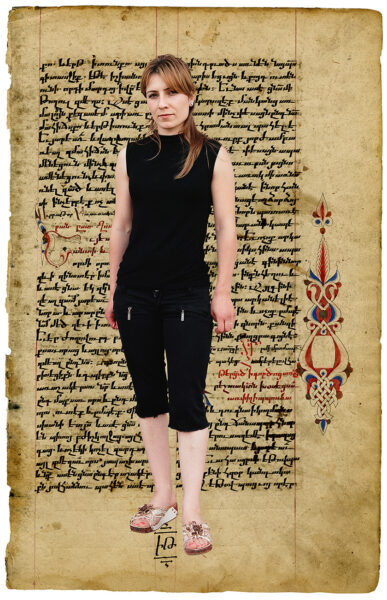

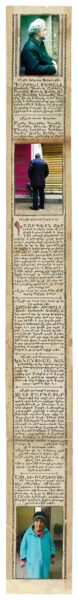

The disparate corners of the diaspora and Armenia, coming together as a whole to represent the Armenian nation in its totality, are formed by photos from Los Angeles, Beirut and Shushi. Along the way, Oshagan deploys several dualities among the photos: black and white photos are spliced into and color collages; photographs are inserted into ancient scrolls and Shushi residents’ larger-than-life portraits are superimposed on ancient manuscripts, some by the famed illuminator, Toros Roslin (1210-1270).

The result is both beautiful and melancholy, showing images from diasporas that once were powerful or simply existed, but are either decimated or gone altogether.

Interviewed at his home in Los Angeles, Oshagan, who is both a photographer and installation artist, said, “A lot of the series deal with different crossings of different types of borders,” such as “the Shushi portraits, where you have residents who are no longer living on their indigenous lands and Armenian manuscripts in the background. There is a border crossing there by Azerbaijan. It is a physical and real border crossing that has caused them to be refugees.”

The Shushi photos are so large that the viewer feels they are seeing these people face to face. We know that these folks are not in Shushi now and wonder: Just where are they? Have those two young boys with their arms around each other’s shoulders fought in the war? Are they safe? So many questions.

“The two boys, they are cousins. One of the brothers died in the war and the rest of the family has fled to Stepanakert. It is really heartbreaking when you think about it and think about our own history. We connect to it in a very visceral way,” he said.