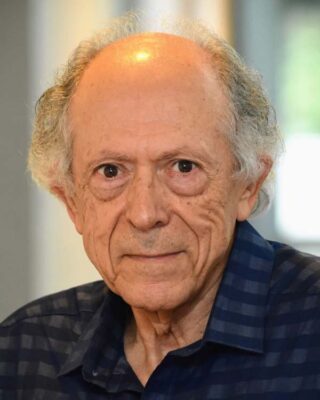

LOS ANGELES — Two of the most renowned scholars of Armenian medieval literature were hosted in conversation on April 1 by the Ararat-Eskijian Museum in Los Angeles. Dr. Abraham Terian, Professor Emeritus of Armenian Theology and Patristics of St. Nersess Seminary, and Dr. S. Peter Cowe, Narekatsi Professor of Armenian Studies at UCLA, discussed a mutual interest of theirs, the Book of Lamentations of St. Gregory of Narek, which has recently been translated and annotated in a critical edition by the former.

The magnum opus of 10th-century monk and poet Gregory of Narek, who was a member of the brotherhood of Narek Monastery near the southern shore of Lake Van in present-day Turkey, this famous book of heartfelt prayers to God rendered in poetic verse is considered by many scholars as the greatest work in the history of Armenian literature. Referred to as “Book of Prayers,” “Book of Lamentations,” (a translation of Madyan Voghperkoutyan), and other titles, it has been beloved by generations of Armenian faithful under the simple name “Narek.” Terian opines that “Penitential Prayers” is a more correct title than “Lamentations” but ultimately he went with a title based on the incipit that is found before each of the 95 prayers: ի խորոց սրտի խօսք ընդ Աստուծոյ (Speaking with God From the Depths of the Heart).

Now, a new scholarly edition in English, From the Depths of the Heart, translated and annotated by Terian, makes this work, which has informed the spirituality of the Armenian Apostolic Church since its completion around the year 1003, much more accessible to the world. The translation was published in 2002 by the Liturgical Press, a Roman Catholic publishing house in Minnesota.

Upbringing in an Armenian Convent

Terian and Cowe began their discussion with the story of Terian’s upbringing in the Armenian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem and with recollections of their early acquaintance when Cowe was a graduate student at Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Terian was born to a family whose ancestors had for generations served as tailors to the monks of the Brotherhood of St. James. As such, the family’s quarters were the closest to the St. James Cathedral, the Armenian Quarter’s main church – so close, in fact, that the church’s interior was on the other side of one of the walls of their apartment. Terian attended services often and could also hear them as a boy from his home, the singing of the priests and deacons coming through the walls. In such a quasi-medieval environment, where all the liturgical services of the Armenian Church were constantly being performed, Terian was imbued with the cadences of Classical Armenian hymns and prayers as a young child, giving him a familiarity with the language that would eventually become the basis of his scholarly career.