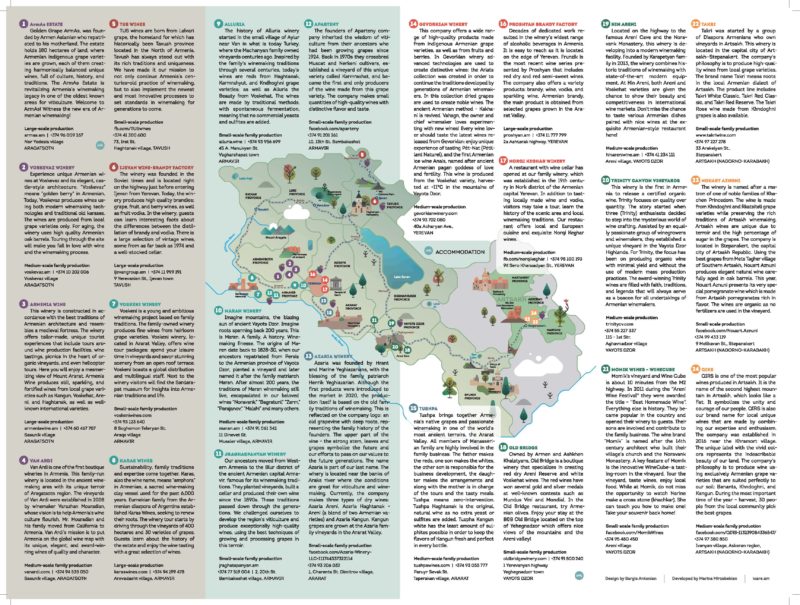

WATERTOWN — It is no secret that the oldest known winery in the world, dating from somewhere between 4100 and 4000 B.C., exists on the territory of the Republic of Armenia (in Areni), yet contemporary Armenian winemaking only recently has experienced a renaissance after a retreat in the Soviet period. Wine now produced in various regions of Armenia and Artsakh is attracting more attention domestically and internationally. The EVN Wine Academy, affiliated with the International Center for Agribusiness Research and Education (ICARE), just issued the second edition of the “Wine Map of Armenia” to facilitate finding some of the more unique wineries.

Marina Mirzabekian, who works parttime for ICARE, collaborated with Sargis Antonian, a graphics designer, to prepare this map. She said that Armenia’s neighbor Georgia has had for some years now a map representing the main wine-producing areas of that country, and that gave ICARE the idea to do an Armenian one in 2021.

There are over 100 wineries in Armenia and Artsakh, so this is far too many to place on a map. In fact, only 24 wineries of Armenia and Artsakh are included in the map. Mirzabekian said that the majority of the wineries chosen to be highlighted have their own vineyards and produce their own wines, but most importantly, the ones that were selected also accept guests and offer a special touristic experience.

She said, “We visited all the wineries we included in order to assess their quality, and the focus was on the small and medium wineries because they are the ones that need the visibility and recognition.” They tend to be family-owned and family-run. The large wineries, some of which can practically be called factories, are well established and do not need extra promotion, she continued, so only a few have been included. Many export, especially to Russia.

In future editions, if there are some new small wineries with decent quality wine, they will replace some of the big wineries on the map, since the space in the map is limited.

The first edition of the map included more wineries in Artsakh, but a good number were lost as a result of the 2020 war, leaving only three Artsakh sites for the second edition to depict which still consistently produce wine and accept guests.