By Alin K. Gregorian

Mirror-Spectator Staff

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Dr. Sebouh D. Aslanian, on Wednesday, September 14, brought the Armenians of New Julfa in Iran to life during a talk at Harvard University that was crammed with facts, but witty and fast-paced. He turned what could be a history lesson into a bird’s-eye-view of the small- yet-plucky community which has left its mark around the world.

The lecture, his first since he took over for the recently-retired Prof. Richard Hovannisian at UCLA, was named after his book, From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: The Global Trade Networks of Armenian Merchants from New Julfa.

Immediately after starting the lecture, Aslanian pleasantly surprised those assembled by joking that he was just saying enough to whet the audience’s appetites so that they would purchase his book and then in turn, through brisk sales, help quicken the arrival of the paperback edition. From that point on, he had the audience’s complete attention.

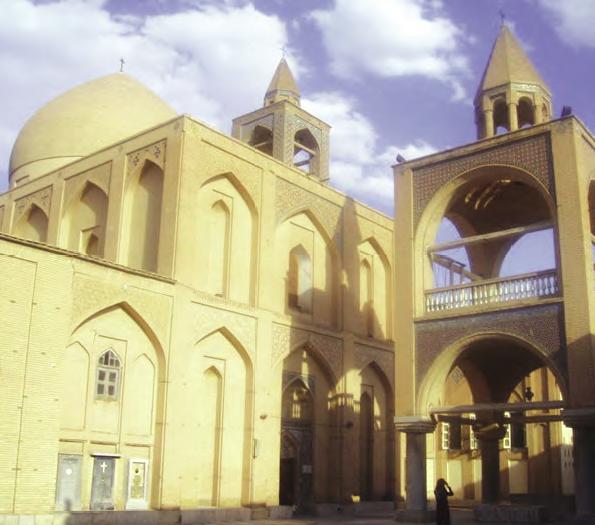

Aslanian’s focus is the Armenians of New Julfa, Iran, a community of traders whose span reached from Venice to India to Mexico. That community was created artificially, as the original Julfans were forcibly brought over to Persia (Iran) from Julfa in Nakhijevan, by Persian ruler Shah Abbas I, in order to bring to Persia the skills (and profits) of these silk and gem traders. The approximate years that the community was practicing its global trade was from 1622 to 1750.

Aslanian spoke admiringly of how these newcomers to Iran thrived not long after their arrival. In fact, this ability to adapt became one reason why they were so successful in living anywhere in the world.